Difference between revisions of "Forest Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences"

| (239 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | =Class Admin= | |

| − | + | ==[[Forest_ErrorAnalysis_Syllabus]]== | |

| − | + | ==Homework== | |

Homework is due at the beginning of class on the assigned day. If you have a documented excuse for your absence, then you will have 24 hours to hand in the homework after being released by your doctor. | Homework is due at the beginning of class on the assigned day. If you have a documented excuse for your absence, then you will have 24 hours to hand in the homework after being released by your doctor. | ||

| − | + | == Class Policies== | |

http://wiki.iac.isu.edu/index.php/Forest_Class_Policies | http://wiki.iac.isu.edu/index.php/Forest_Class_Policies | ||

| − | + | == Instructional Objectives == | |

;Course Catalog Description | ;Course Catalog Description | ||

| − | : Error Analysis for the Physics Sciences 3 credits. Lecture course with computation requirements. Topics include: Error propagation, Probability Distributions, Least Squares fit, multiple regression, | + | : Error Analysis for the Physics Sciences 3 credits. Lecture course with computation requirements. Topics include: Error propagation, Probability Distributions, Least Squares fit, multiple regression, goodness of fit, covariance and correlations. |

Prequisites:Math 360. | Prequisites:Math 360. | ||

;Course Description | ;Course Description | ||

| − | : The course | + | : The application of statistical inference and hypothesis testing will be the main focus of this course for students who are senior level undergraduates or beginning graduate students. The course begins by introducing the basic skills of error analysis and then proceeds to describe fundamental methods comparing measurements and models. A freely available data analysis package known as ROOT will be used. Some programming skills will be needed using C/C++ but a limited amount of experience is assumed. |

| − | = | + | ==Objectives and Outcomes== |

| − | + | [[Forest_ErrorAnalysis_ObjectivesnOutcomes]] | |

| − | |||

| − | X \pm Y = X(Y) | + | ==Suggested Text== |

| + | [http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_ss?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=0079112439&x=12&y=19 Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences by Philip Bevington] ISBN: | ||

| + | 0079112439 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Homework= | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[TF_ErrAna_Homework]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Class Labs = | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[TF_ErrAna_InClassLab]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =Systematic and Random Uncertainties= | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Although the name of the class is "Error Analysis" for historical purposes, a more accurate description would be "Uncertainty Analysis". "Error" usually means a mistake is made while "Uncertainty" is a measure of how confident you are in a measurement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Accuracy -vs- Precision== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Accuracy | ||

| + | :How close does an experiment come to the correct result | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Precision | ||

| + | :A measure of how exact the result is determined. No reference is made to what the result means. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Systematic Error== | ||

| + | |||

| + | What is a systematic error? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A class of errors which result in reproducible mistakes due to equipment bias or a bias related to its use by the observer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Example: A ruler | ||

| + | |||

| + | a.) A ruler could be shorter or longer because of temperature fluctuations | ||

| + | |||

| + | b.) An observer could be viewing the markings at a glancing angle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In this case a systematic error is more of a mistake than an uncertainty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In some cases you can correct for the systematic error. In the above Ruler example you can measure how the ruler's length changes with temperature. You can then correct this systematic error by measuring the temperature of the ruler during the distance measurement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Correction Example: | ||

| + | |||

| + | A ruler is calibrated at 25 C an has an expansion coefficient of (0.0005 <math>\pm</math> 0.0001 m/C. | ||

| + | |||

| + | You measure the length of a wire at 20 C and find that on average it is <math>1.982 \pm 0.0001</math> m long. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This means that the 1 m ruler is really (1-(20-25 C)(0.0005 m/C)) = 0.99775 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | So the correction becomes | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1.982 *( 0.99775) =1.977 m | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Note: The numbers above without decimal points are integers. Integers have infinite precision. We will discuss the propagation of the errors above in a different chapter. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Error from bad technique: | ||

| + | |||

| + | After repeating the experiment several times the observer discovers that he had a tendency to read the meter stick at an angle and not from directly above. After investigating this misread with repeated measurements the observer estimates that on average he will misread the meter stick by 2 mm. This is now a systematic error that is estimated using random statistics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Reporting Uncertainties== | ||

| + | ===Notation=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | X <math>\pm</math> Y = X(Y) | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Significant Figures and Round off== | ||

| + | === Significant figures=== | ||

| + | ;Most Significant digit | ||

| + | : The leftmost non-zero digit is the most significant digit of a reported value | ||

| + | |||

| + | ; Least Significant digit | ||

| + | : The least significant digit is identified using the following criteria | ||

| + | :1.) If there is no decimal point, then the rightmost digit is the least significant digit. | ||

| + | :2.)If there is a decimal point, then the rightmost digit is the least significant digit, even if it is a zero. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In other words, zero counts as a least significant digit only if it is after the decimal point. So when you report a measurement with a zero in such a position you had better mean it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ; The number of significant digits in a measurement are the number of digits which appear between the least and most significant digits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | examples: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| border="3" cellpadding="20" cellspacing="0" | ||

| + | |Measurement ||most Sig. digit || least Sig. || Num. Sig. Dig. || Scientific Notation | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 5 || 5 || 5 || 1* || <math>5</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 5.0 || 5 || 0 || 2|| <math>5.0 </math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 50 || 5 || 0 || 2*|| <math>5 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 50.1 || 5 || 1 || 3|| <math>5.01 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 0.005001 || 5 || 1 || 4|| <math>5.001\times 10^{-3}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;*Note | ||

| + | :The values of "5" and "50" above are ambiguous unless we use scientific notation in which case we know if the zero is significant or not. Otherwise, integers have infinite precision. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Round Off=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Measurements that are reported which are based on the calculation of more than one measured quantity must have the same number of significant digits as the quantity with the smallest number of significant digits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To accomplish this you will need to round of the final measured value that is reported. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To round off a number you: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1.) Increment the least significant digit by one if the digit below it (in significance) is greater than 5. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2.) Do nothing if the digit below it (in significance) is less than 5. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then truncate the remaining digits below the least significant digit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;What happens if the next significant digit below the least significant digit is exactly 5? | ||

| + | |||

| + | To avoid a systematic error involving round off you would ideally randomly decide to just truncate or increment. If your calculation is not on a computer with a random number generator, or you don't have one handy, then the typical technique is to increment the least significant digit if it is odd (or even) and truncate it if it is even (or odd). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Examples: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The table below has three entries; the final value calculated from several measured quantities, the number of significant digits for the measurement with the smallest number of significant digits, and the rounded off value properly reported using scientific notation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| border="3" cellpadding="20" cellspacing="0" | ||

| + | |Value || Sig. digits || Rounded off value | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 12.34 || 3 || <math>1.23 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 12.36 || 3 || <math>1.24 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 12.35 || 3 || <math>1.24 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 12.35 || 2 || <math>1.2 \times 10^{1}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Statistics abuse== | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28507867 | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53814054 | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Forest_StatBadExamples]] | ||

=Statistical Distributions= | =Statistical Distributions= | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[Forest_ErrAna_StatDist]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

=Propagation of Uncertainties= | =Propagation of Uncertainties= | ||

| + | [[TF_ErrorAna_PropOfErr]] | ||

| + | =Statistical inference= | ||

| − | + | [[TF_ErrorAna_StatInference]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.09077 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Byron Roe | |

| − | + | (Submitted on 30 Jun 2015) | |

| − | + | The problem of fitting an event distribution when the total expected number of events is not fixed, keeps appearing in experimental studies. In a chi-square fit, if overall normalization is one of the parameters parameters to be fit, the fitted curve may be seriously low with respect to the data points, sometimes below all of them. This problem and the solution for it are well known within the statistics community, but, apparently, not well known among some of the physics community. The purpose of this note is didactic, to explain the cause of the problem and the easy and elegant solution. The solution is to use maximum likelihood instead of chi-square. The essential difference between the two approaches is that maximum likelihood uses the normalization of each term in the chi-square assuming it is a normal distribution, 1/sqrt(2 pi sigma-square). In addition, the normalization is applied to the theoretical expectation not to the data. In the present note we illustrate what goes wrong and how maximum likelihood fixes the problem in a very simple toy example which illustrates the problem clearly and is the appropriate physics model for event histograms. We then note how a simple modification to the chi-square method gives a result identical to the maximum likelihood method. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

| Line 65: | Line 197: | ||

2.)[http://www.uscibooks.com/taylornb.htm An Introduction to Error Analysis, John R. Taylor] ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0 | 2.)[http://www.uscibooks.com/taylornb.htm An Introduction to Error Analysis, John R. Taylor] ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3.) [http://root.cern.ch ROOT: An Analysis Framework] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 4.) [http://nedwww.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/Sept01/Orear/frames.html Orear, "Notes on Statistics for Physicists"] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 5.) Statistical Methods for Engineers and Scientists, Robert M. Bethea, Benjamin S. Duran, and Thomas L. Boullion, Marcel Dekker Inc, New York, (1985), QA 276.B425 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 6.) Data Analysis for Scientists and Engineers, Stuart L. Meyer, John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York, (1975), QA 276.M437 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 7.) Syntax for ROOT Math Functions | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://root.cern.ch/root/htmldoc/MATH_Index.html | ||

| + | |||

| + | =ROOT comands= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==A ROOT Primer== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Download=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can usually download the ROOT software for multiple platforms for free at the URL below | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://root.cern.ch | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is a lot of documentation which may be reached through the above URL as well | ||

| + | |||

| + | some things that may need to be installed | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install git | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install make | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install libx11-dev | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install libxpm-dev | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install libxft-dev | ||

| + | |||

| + | sudo apt-get install libxext-dev | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====install==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | git clone http://github.com/root-project/root.git | ||

| + | |||

| + | cd root | ||

| + | |||

| + | git checkout -b v6-10-08 v6-10-08 | ||

| + | |||

| + | cd .. | ||

| + | |||

| + | mkdir v6-10-08 | ||

| + | |||

| + | cd v6-10-08 | ||

| + | |||

| + | cmake -D mysql:BOOL=OFF ../root | ||

| + | |||

| + | cmake --build . | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Setup the environment=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is an environmental variable which is usually needed on most platforms in order to run ROOT. I will just give the commands for setting things up under the bash shell running on the UNIX platform. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Set the variable ROOTSYS to point to the directory used to install ROOT | ||

| + | |||

| + | export ROOTSYS=~/src/ROOT/root | ||

| + | |||

| + | OR | ||

| + | |||

| + | source ~/src/ROOT/root/bin/thisroot.sh | ||

| + | |||

| + | I have installed the latest version of ROOT in the subdirectory ~/src/ROOT/root. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | You can now run the program from any subdirectory with the command | ||

| + | |||

| + | $ROOTSYS/bin/root | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you want to compile programs which use ROOT libraries you should probably put the "bin" subdirectory under ROOTSYS in your path as well as define a variable pointing to the subdirectory used to store all the ROOT libraries (usually $ROOTSYS/lib). | ||

| + | |||

| + | PATH=$PATH:$ROOTSYS/bin | ||

| + | |||

| + | export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$LD_LIBRARY_PATH:$ROOTSYS/lib | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Other UNIX shell and operating systems will have different syntax for doing the same thing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Starting and exiting ROOT=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Starting and exiting the ROOT program may be the next important thing to learn. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As already mentioned above you can start ROOT by executing the command | ||

| + | |||

| + | $ROOTSYS/bin/root | ||

| + | |||

| + | from an operating system command shell. You will see a "splash" screen appear and go away after a few seconds. Your command shell is now a ROOT command interpreter known as CINT which has the command prompt "root[0]". You can type commands within this environment such as the command below to exit the ROOT program. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To EXIT the program just type | ||

| + | |||

| + | .q | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Starting the ROOT Browser (GUI)=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | By now most computer users are accustomed to Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) for application. You can launch a GUI from within the ROOT command interpreter interface with the command | ||

| + | |||

| + | new TBrowser(); | ||

| + | |||

| + | A window should open with pull down menus. You can now exit root by selecting "Quit ROOT" from the pull down menu labeled "File" in the upper left part of the GUI window. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==plotting Probability Distributions in ROOT== | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://project-mathlibs.web.cern.ch/project-mathlibs/sw/html/group__PdfFunc.html | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Binomial distribution is plotted below for the case of flipping a coin 60 times (n=60,p=1/2) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;You can see the integral , Mean and , RMS by right clicking on the Statistics box and choosing "SetOptStat". A menu box pops up and you enter the binary code "1001111" (without the quotes). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | root [0] Int_t i; | ||

| + | root [1] Double_t x | ||

| + | root [2] TH1F *B30=new TH1F("B30","B30",100,0,100) | ||

| + | root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::binomial_pdf(i,0.5,60);B30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | root [4] B30->Draw(); | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can continue creating plots of the various distributions with the commands | ||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | root [2] TH1F *P30=new TH1F("P30","P30",100,0,100) | ||

| + | root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::poisson_pdf(i,30);P30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | root [4] P30->Draw("same"); | ||

| + | root [2] TH1F *G30=new TH1F("G30","G30",100,0,100) | ||

| + | root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::gaussian_pdf(i,3.8729,30);G30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | root [4] G30->Draw("same"); | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above commands created the plot below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Forest_EA_BinPosGaus_Mean30.png| 200 px]] | ||

| + | [[File:Forest_EA_BinPosGaus_Mean30.eps]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Note: I set each distribution to correspond to a mean (<math>\mu</math>) of 30. The <math>\sigma^2</math> of the Binomial distribution is <math>np(1-p)</math> = 60(1/2)(1/2) = 15. The <math>\sigma^2</math> of the Poisson distribution is defined to equal the mean <math>\mu=30</math>. I intentionally set the mean and sigma of the Gaussian to agree with the Binomial. As you can see the Binomial and Gaussian lay on top of each other while the Poisson is wider. The Gaussian will lay on top of the Poisson if you change its <math>\sigma</math> to 5.477 | ||

| + | |||

| + | for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::gaussian_pdf(i,5.477,30);G30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;Also Note: The Gaussian distribution can be used to represent the Binomial and Poisson distributions when the average is large ( ie:<math>\mu > 10</math>). The Poisson distribution, though, is an approximation to the Binomial distribution for the special case where the average number of successes is small ( <math>\mu << n</math> because <math>p <<1</math>) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | Int_t i; | ||

| + | Double_t x | ||

| + | TH1F *B30=new TH1F("B30","B30",100,0,10); | ||

| + | TH1F *P30=new TH1F("P30","P30",100,0,10); | ||

| + | for(i=0;i<10;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::binomial_pdf(i,0.1,10);B30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | for(i=0;i<10;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::poisson_pdf(i,1);P30->Fill(i,x);} | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Forest_EA_BinPos_Mean1.png| 200 px]] | ||

| + | [[File:Forest_EA_BinPos_Mean1.eps]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other probability distribution functions | ||

| + | |||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | double beta_pdf(double x, double a, double b) | ||

| + | double binomial_pdf(unsigned int k, double p, unsigned int n) | ||

| + | double breitwigner_pdf(double x, double gamma, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double cauchy_pdf(double x, double b = 1, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double chisquared_pdf(double x, double r, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double exponential_pdf(double x, double lambda, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double fdistribution_pdf(double x, double n, double m, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double gamma_pdf(double x, double alpha, double theta, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double gaussian_pdf(double x, double sigma = 1, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double landau_pdf(double x, double s = 1, double x0 = 0.) | ||

| + | double lognormal_pdf(double x, double m, double s, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double normal_pdf(double x, double sigma = 1, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double poisson_pdf(unsigned int n, double mu) | ||

| + | double tdistribution_pdf(double x, double r, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | double uniform_pdf(double x, double a, double b, double x0 = 0) | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Sampling from Prob Dist in ROOT== | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can also use ROOT to generate random numbers according to a given probability distribution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the example generates 1000 random numbers from a Poisson Parent population with a mean of 10 | ||

| + | |||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | root [0] TRandom r | ||

| + | root [1] TH1F *P10=new TH1F("P10","P10",100,0,100) | ||

| + | root [2] for(i=0;i<10000;i++) P10->Fill(r.Poisson(30)); | ||

| + | Warning: Automatic variable i is allocated (tmpfile):1: | ||

| + | root [3] P10->Draw(); | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other possibilities | ||

| + | |||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | Gaussian with a mean of 30 and sigma of 5 | ||

| + | root [1] TH1F *G10=new TH1F("G10","G10",100,0,100) | ||

| + | root [2] for(i=0;i<10000;i++) G10->Fill(r.Gauss(30,5)); //mean of 30 and sigma of 5 | ||

| + | root [3] G10->Draw("same"); | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is also | ||

| + | |||

| + | G10->Fill(r.Uniform(20,50)); // Generates a uniform distribution between 20 and 50 | ||

| + | |||

| + | G10->Fill(r.Exp(30)); // exponential distribution with a mean of 30 | ||

| + | |||

| + | G10->Fill(r.Landau(30,5)); // Landau distribution with a mean of 30 and sigma of 5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | G10->Fill(r.BreitWigner(30,5)); mean of 30 and gamma of 5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =Final Exam= | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Final exam will be to write a report describing the analysis of the data in [[TF_ErrAna_InClassLab#Lab_16]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Grading Scheme: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Grid Search method results | ||

| + | |||

| + | 10% Parameter values | ||

| + | |||

| + | 20% Parameter errors | ||

| + | |||

| + | 30% Probability fit is correct | ||

| + | |||

| + | 40% Grammatically correct written explanation of the data analysis with publication quality plots | ||

| + | |||

| + | Report due in my office and source code in my e-mail by Friday, May 8, 2:30 pm (MST) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Report length is between 3 and 15 pages all inclusive. Min Font Size is 12 pt, 1.5 spacing of lines, max margin 2". | ||

| + | |||

| + | =WIP= | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[TF_ErrorAnalysis_WIP]] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:11, 29 April 2020

Class Admin

Forest_ErrorAnalysis_Syllabus

Homework

Homework is due at the beginning of class on the assigned day. If you have a documented excuse for your absence, then you will have 24 hours to hand in the homework after being released by your doctor.

Class Policies

http://wiki.iac.isu.edu/index.php/Forest_Class_Policies

Instructional Objectives

- Course Catalog Description

- Error Analysis for the Physics Sciences 3 credits. Lecture course with computation requirements. Topics include: Error propagation, Probability Distributions, Least Squares fit, multiple regression, goodness of fit, covariance and correlations.

Prequisites:Math 360.

- Course Description

- The application of statistical inference and hypothesis testing will be the main focus of this course for students who are senior level undergraduates or beginning graduate students. The course begins by introducing the basic skills of error analysis and then proceeds to describe fundamental methods comparing measurements and models. A freely available data analysis package known as ROOT will be used. Some programming skills will be needed using C/C++ but a limited amount of experience is assumed.

Objectives and Outcomes

Forest_ErrorAnalysis_ObjectivesnOutcomes

Suggested Text

Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences by Philip Bevington ISBN: 0079112439

Homework

Class Labs

Systematic and Random Uncertainties

Although the name of the class is "Error Analysis" for historical purposes, a more accurate description would be "Uncertainty Analysis". "Error" usually means a mistake is made while "Uncertainty" is a measure of how confident you are in a measurement.

Accuracy -vs- Precision

- Accuracy

- How close does an experiment come to the correct result

- Precision

- A measure of how exact the result is determined. No reference is made to what the result means.

Systematic Error

What is a systematic error?

A class of errors which result in reproducible mistakes due to equipment bias or a bias related to its use by the observer.

Example: A ruler

a.) A ruler could be shorter or longer because of temperature fluctuations

b.) An observer could be viewing the markings at a glancing angle.

In this case a systematic error is more of a mistake than an uncertainty.

In some cases you can correct for the systematic error. In the above Ruler example you can measure how the ruler's length changes with temperature. You can then correct this systematic error by measuring the temperature of the ruler during the distance measurement.

Correction Example:

A ruler is calibrated at 25 C an has an expansion coefficient of (0.0005 0.0001 m/C.

You measure the length of a wire at 20 C and find that on average it is m long.

This means that the 1 m ruler is really (1-(20-25 C)(0.0005 m/C)) = 0.99775

So the correction becomes

1.982 *( 0.99775) =1.977 m

- Note

- The numbers above without decimal points are integers. Integers have infinite precision. We will discuss the propagation of the errors above in a different chapter.

Error from bad technique:

After repeating the experiment several times the observer discovers that he had a tendency to read the meter stick at an angle and not from directly above. After investigating this misread with repeated measurements the observer estimates that on average he will misread the meter stick by 2 mm. This is now a systematic error that is estimated using random statistics.

Reporting Uncertainties

Notation

X Y = X(Y)

Significant Figures and Round off

Significant figures

- Most Significant digit

- The leftmost non-zero digit is the most significant digit of a reported value

- Least Significant digit

- The least significant digit is identified using the following criteria

- 1.) If there is no decimal point, then the rightmost digit is the least significant digit.

- 2.)If there is a decimal point, then the rightmost digit is the least significant digit, even if it is a zero.

In other words, zero counts as a least significant digit only if it is after the decimal point. So when you report a measurement with a zero in such a position you had better mean it.

- The number of significant digits in a measurement are the number of digits which appear between the least and most significant digits.

examples:

| Measurement | most Sig. digit | least Sig. | Num. Sig. Dig. | Scientific Notation |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 1* | |

| 5.0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | |

| 50 | 5 | 0 | 2* | |

| 50.1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | |

| 0.005001 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

- Note

- The values of "5" and "50" above are ambiguous unless we use scientific notation in which case we know if the zero is significant or not. Otherwise, integers have infinite precision.

Round Off

Measurements that are reported which are based on the calculation of more than one measured quantity must have the same number of significant digits as the quantity with the smallest number of significant digits.

To accomplish this you will need to round of the final measured value that is reported.

To round off a number you:

1.) Increment the least significant digit by one if the digit below it (in significance) is greater than 5.

2.) Do nothing if the digit below it (in significance) is less than 5.

Then truncate the remaining digits below the least significant digit.

- What happens if the next significant digit below the least significant digit is exactly 5?

To avoid a systematic error involving round off you would ideally randomly decide to just truncate or increment. If your calculation is not on a computer with a random number generator, or you don't have one handy, then the typical technique is to increment the least significant digit if it is odd (or even) and truncate it if it is even (or odd).

- Examples

The table below has three entries; the final value calculated from several measured quantities, the number of significant digits for the measurement with the smallest number of significant digits, and the rounded off value properly reported using scientific notation.

| Value | Sig. digits | Rounded off value |

| 12.34 | 3 | |

| 12.36 | 3 | |

| 12.35 | 3 | |

| 12.35 | 2 |

Statistics abuse

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28507867

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53814054

Statistical Distributions

Propagation of Uncertainties

Statistical inference

http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.09077

Byron Roe (Submitted on 30 Jun 2015)

The problem of fitting an event distribution when the total expected number of events is not fixed, keeps appearing in experimental studies. In a chi-square fit, if overall normalization is one of the parameters parameters to be fit, the fitted curve may be seriously low with respect to the data points, sometimes below all of them. This problem and the solution for it are well known within the statistics community, but, apparently, not well known among some of the physics community. The purpose of this note is didactic, to explain the cause of the problem and the easy and elegant solution. The solution is to use maximum likelihood instead of chi-square. The essential difference between the two approaches is that maximum likelihood uses the normalization of each term in the chi-square assuming it is a normal distribution, 1/sqrt(2 pi sigma-square). In addition, the normalization is applied to the theoretical expectation not to the data. In the present note we illustrate what goes wrong and how maximum likelihood fixes the problem in a very simple toy example which illustrates the problem clearly and is the appropriate physics model for event histograms. We then note how a simple modification to the chi-square method gives a result identical to the maximum likelihood method.

References

1.) "Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences", Philip R. Bevington, ISBN-10: 0079112439, ISBN-13: 9780079112439

CPP programs for Bevington

2.)An Introduction to Error Analysis, John R. Taylor ISBN 978-0-935702-75-0

3.) ROOT: An Analysis Framework

4.) Orear, "Notes on Statistics for Physicists"

5.) Statistical Methods for Engineers and Scientists, Robert M. Bethea, Benjamin S. Duran, and Thomas L. Boullion, Marcel Dekker Inc, New York, (1985), QA 276.B425

6.) Data Analysis for Scientists and Engineers, Stuart L. Meyer, John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York, (1975), QA 276.M437

7.) Syntax for ROOT Math Functions

http://root.cern.ch/root/htmldoc/MATH_Index.html

ROOT comands

A ROOT Primer

Download

You can usually download the ROOT software for multiple platforms for free at the URL below

There is a lot of documentation which may be reached through the above URL as well

some things that may need to be installed

sudo apt-get install git

sudo apt-get install make

sudo apt-get install libx11-dev

sudo apt-get install libxpm-dev

sudo apt-get install libxft-dev

sudo apt-get install libxext-dev

install

git clone http://github.com/root-project/root.git

cd root

git checkout -b v6-10-08 v6-10-08

cd ..

mkdir v6-10-08

cd v6-10-08

cmake -D mysql:BOOL=OFF ../root

cmake --build .

Setup the environment

There is an environmental variable which is usually needed on most platforms in order to run ROOT. I will just give the commands for setting things up under the bash shell running on the UNIX platform.

- Set the variable ROOTSYS to point to the directory used to install ROOT

export ROOTSYS=~/src/ROOT/root

OR

source ~/src/ROOT/root/bin/thisroot.sh

I have installed the latest version of ROOT in the subdirectory ~/src/ROOT/root.

You can now run the program from any subdirectory with the command

$ROOTSYS/bin/root

If you want to compile programs which use ROOT libraries you should probably put the "bin" subdirectory under ROOTSYS in your path as well as define a variable pointing to the subdirectory used to store all the ROOT libraries (usually $ROOTSYS/lib).

PATH=$PATH:$ROOTSYS/bin

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$LD_LIBRARY_PATH:$ROOTSYS/lib

Other UNIX shell and operating systems will have different syntax for doing the same thing.

Starting and exiting ROOT

Starting and exiting the ROOT program may be the next important thing to learn.

As already mentioned above you can start ROOT by executing the command

$ROOTSYS/bin/root

from an operating system command shell. You will see a "splash" screen appear and go away after a few seconds. Your command shell is now a ROOT command interpreter known as CINT which has the command prompt "root[0]". You can type commands within this environment such as the command below to exit the ROOT program.

To EXIT the program just type

.q

Starting the ROOT Browser (GUI)

By now most computer users are accustomed to Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) for application. You can launch a GUI from within the ROOT command interpreter interface with the command

new TBrowser();

A window should open with pull down menus. You can now exit root by selecting "Quit ROOT" from the pull down menu labeled "File" in the upper left part of the GUI window.

plotting Probability Distributions in ROOT

http://project-mathlibs.web.cern.ch/project-mathlibs/sw/html/group__PdfFunc.html

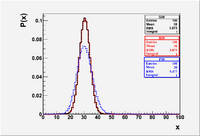

The Binomial distribution is plotted below for the case of flipping a coin 60 times (n=60,p=1/2)

- You can see the integral , Mean and , RMS by right clicking on the Statistics box and choosing "SetOptStat". A menu box pops up and you enter the binary code "1001111" (without the quotes).

root [0] Int_t i;

root [1] Double_t x

root [2] TH1F *B30=new TH1F("B30","B30",100,0,100)

root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::binomial_pdf(i,0.5,60);B30->Fill(i,x);}

root [4] B30->Draw();

You can continue creating plots of the various distributions with the commands

root [2] TH1F *P30=new TH1F("P30","P30",100,0,100)

root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::poisson_pdf(i,30);P30->Fill(i,x);}

root [4] P30->Draw("same");

root [2] TH1F *G30=new TH1F("G30","G30",100,0,100)

root [3] for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::gaussian_pdf(i,3.8729,30);G30->Fill(i,x);}

root [4] G30->Draw("same");

The above commands created the plot below.

File:Forest EA BinPosGaus Mean30.eps

File:Forest EA BinPosGaus Mean30.eps

- Note

- I set each distribution to correspond to a mean () of 30. The of the Binomial distribution is = 60(1/2)(1/2) = 15. The of the Poisson distribution is defined to equal the mean . I intentionally set the mean and sigma of the Gaussian to agree with the Binomial. As you can see the Binomial and Gaussian lay on top of each other while the Poisson is wider. The Gaussian will lay on top of the Poisson if you change its to 5.477

for(i=0;i<100;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::gaussian_pdf(i,5.477,30);G30->Fill(i,x);}

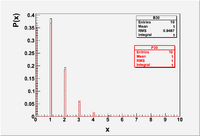

- Also Note

- The Gaussian distribution can be used to represent the Binomial and Poisson distributions when the average is large ( ie:). The Poisson distribution, though, is an approximation to the Binomial distribution for the special case where the average number of successes is small ( because )

Int_t i;

Double_t x

TH1F *B30=new TH1F("B30","B30",100,0,10);

TH1F *P30=new TH1F("P30","P30",100,0,10);

for(i=0;i<10;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::binomial_pdf(i,0.1,10);B30->Fill(i,x);}

for(i=0;i<10;i++) {x=ROOT::Math::poisson_pdf(i,1);P30->Fill(i,x);}

File:Forest EA BinPos Mean1.eps

File:Forest EA BinPos Mean1.eps

Other probability distribution functions

double beta_pdf(double x, double a, double b) double binomial_pdf(unsigned int k, double p, unsigned int n) double breitwigner_pdf(double x, double gamma, double x0 = 0) double cauchy_pdf(double x, double b = 1, double x0 = 0) double chisquared_pdf(double x, double r, double x0 = 0) double exponential_pdf(double x, double lambda, double x0 = 0) double fdistribution_pdf(double x, double n, double m, double x0 = 0) double gamma_pdf(double x, double alpha, double theta, double x0 = 0) double gaussian_pdf(double x, double sigma = 1, double x0 = 0) double landau_pdf(double x, double s = 1, double x0 = 0.) double lognormal_pdf(double x, double m, double s, double x0 = 0) double normal_pdf(double x, double sigma = 1, double x0 = 0) double poisson_pdf(unsigned int n, double mu) double tdistribution_pdf(double x, double r, double x0 = 0) double uniform_pdf(double x, double a, double b, double x0 = 0)

Sampling from Prob Dist in ROOT

You can also use ROOT to generate random numbers according to a given probability distribution.

In the example generates 1000 random numbers from a Poisson Parent population with a mean of 10

root [0] TRandom r

root [1] TH1F *P10=new TH1F("P10","P10",100,0,100)

root [2] for(i=0;i<10000;i++) P10->Fill(r.Poisson(30));

Warning: Automatic variable i is allocated (tmpfile):1:

root [3] P10->Draw();

Other possibilities

Gaussian with a mean of 30 and sigma of 5

root [1] TH1F *G10=new TH1F("G10","G10",100,0,100)

root [2] for(i=0;i<10000;i++) G10->Fill(r.Gauss(30,5)); //mean of 30 and sigma of 5

root [3] G10->Draw("same");

There is also

G10->Fill(r.Uniform(20,50)); // Generates a uniform distribution between 20 and 50

G10->Fill(r.Exp(30)); // exponential distribution with a mean of 30

G10->Fill(r.Landau(30,5)); // Landau distribution with a mean of 30 and sigma of 5

G10->Fill(r.BreitWigner(30,5)); mean of 30 and gamma of 5

Final Exam

The Final exam will be to write a report describing the analysis of the data in TF_ErrAna_InClassLab#Lab_16

Grading Scheme:

Grid Search method results

10% Parameter values

20% Parameter errors

30% Probability fit is correct

40% Grammatically correct written explanation of the data analysis with publication quality plots

Report due in my office and source code in my e-mail by Friday, May 8, 2:30 pm (MST)

Report length is between 3 and 15 pages all inclusive. Min Font Size is 12 pt, 1.5 spacing of lines, max margin 2".