Difference between revisions of "TF EIM Chapt2"

(→Gain) |

|||

| (18 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 244: | Line 244: | ||

then | then | ||

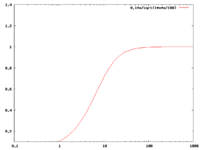

| − | :<math>\frac{V_{out}}{V_{in}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \left ( \frac{\omega}{\omega_b}\right )^2}}</math> | + | :<math>\frac{V_{out}}{V_{in}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \left ( \frac{\omega}{\omega_b}\right )^2}}= \frac{1}{\sqrt 2}</math> |

[[File:TF_EIM_LowPassVoutVin-vs-omega.png|200px]] | [[File:TF_EIM_LowPassVoutVin-vs-omega.png|200px]] | ||

| Line 272: | Line 272: | ||

Based on the above Phasor diagram | Based on the above Phasor diagram | ||

| − | :<math>\tan(\phi) = \left (\frac{R}{\frac{-1}{\omega C}} \right )= \left(\omega RC \right )</math> | + | :<math>\tan(\phi) = \left (\frac{R}{\frac{-1}{\omega C}} \right )= \left(-\omega RC \right )</math> |

=== High Pass Filter=== | === High Pass Filter=== | ||

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

if | if | ||

:<math>\omega_B=\frac{1}{RC}=10</math> | :<math>\omega_B=\frac{1}{RC}=10</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>\phi_{\mbox{Low Pass}} = \tan^{-1} \left ( -\frac{\omega}{\omega_B}\right )</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\phi_{\mbox{High Pass}} = \tan^{-1} \left ( -\frac{\omega_B}{\omega}\right )</math> | ||

{| border="1" |cellpadding="20" cellspacing="0 | {| border="1" |cellpadding="20" cellspacing="0 | ||

| Line 357: | Line 362: | ||

| − | A common and more general technique to solving such a differential equation is to use the solution from the discharging equation (the homogeneous diff. eq.) as a trial solution by | + | A common and more general technique to solving such a differential equation is to use the solution from the discharging equation (the homogeneous diff. eq.) as a trial solution to the charging (non-homogeneous) problem by constructing the linear combination below. |

:<math>Q_{trial} = A + Be^{-t/RC}</math> | :<math>Q_{trial} = A + Be^{-t/RC}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where A & B are constants to e determined | ||

You then substitute this trial solution into the differential equation and apply boundary conditions to determine the coefficients. | You then substitute this trial solution into the differential equation and apply boundary conditions to determine the coefficients. | ||

| + | : <math>\frac{d}{dt} Q+ \frac{1}{RC}Q = \frac{V}{R}</math> | ||

: <math>\frac{d}{dt} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) + \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | : <math>\frac{d}{dt} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) + \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | ||

: <math> \left ( B \frac{-1}{RC}e^{-t/RC} \right ) + \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | : <math> \left ( B \frac{-1}{RC}e^{-t/RC} \right ) + \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A + Be^{-t/RC} \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | ||

: <math>\Rightarrow \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | : <math>\Rightarrow \frac{1}{RC} \left ( A \right ) = \frac{V}{R}</math> | ||

| − | : <math>A = C | + | : <math>A = C V</math> |

To determine the other coefficient you apply the boundary condition that q = 0 when t=0 | To determine the other coefficient you apply the boundary condition that q = 0 when t=0 | ||

| Line 454: | Line 462: | ||

So in essence the inductor acts "like" a resistor which resists the current flow according to the amount of current is changing. | So in essence the inductor acts "like" a resistor which resists the current flow according to the amount of current is changing. | ||

| − | There is an effective | + | There is an effective reactance <math>X_{L}</math> for inductors as there was one for capacitors |

| − | |||

== Inductor Reactance== | == Inductor Reactance== | ||

| Line 473: | Line 480: | ||

: <math>\Rightarrow I(t) = V_0 \frac{sin(\omega t)}{\omega L} + I(0)</math> | : <math>\Rightarrow I(t) = V_0 \frac{sin(\omega t)}{\omega L} + I(0)</math> | ||

| − | + | Assume I(0) =0 and rewrite <math>\sin</math> in terms of a phase shifted <math>\cos</math> | |

: <math>\Rightarrow I(t) = \frac{V_0}{\omega L} cos(\omega t - \pi/2) </math> : V and I are 90 degrees out of phase | : <math>\Rightarrow I(t) = \frac{V_0}{\omega L} cos(\omega t - \pi/2) </math> : V and I are 90 degrees out of phase | ||

| Line 503: | Line 510: | ||

or | or | ||

| − | ::<math>\nu_{LC} = \frac{\omega_{LC}}{2\pi}\frac{1}{2 \pi \sqrt{LC}}</math> | + | ::<math>\nu_{LC} = \frac{\omega_{LC}}{2\pi} = \frac{1}{2 \pi \sqrt{LC}}</math> |

| Line 512: | Line 519: | ||

|<math>L = 33 \mu H</math> and <math>C = 1 \mu F </math> | |<math>L = 33 \mu H</math> and <math>C = 1 \mu F </math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[File:TF_EIM_Impedance_LC_Parallel.png| | + | |[[File:TF_EIM_Impedance_LC_Parallel.png| 400 px]] |

|- | |- | ||

|<math>\Rightarrow \omega = 174077.66</math> rad/s | |<math>\Rightarrow \omega = 174077.66</math> rad/s | ||

| Line 560: | Line 567: | ||

|<math>L = 33 \mu H</math> and <math>C = 1 \mu F </math> and R=200 <math>\Omega</math> | |<math>L = 33 \mu H</math> and <math>C = 1 \mu F </math> and R=200 <math>\Omega</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[File:TF_EIM_LC_paral_Gain.png | | + | |[[File:TF_EIM_LC_paral_Gain.png | 400 px]] |

|- | |- | ||

|<math>\Rightarrow \omega = 174077.66</math> rad/s or <math>\nu = \frac{\omega}{2 \pi} = 27705</math> Hz | |<math>\Rightarrow \omega = 174077.66</math> rad/s or <math>\nu = \frac{\omega}{2 \pi} = 27705</math> Hz | ||

| Line 577: | Line 584: | ||

| − | ;Bandwith: The most common definition for the Bandwidth of this circuit is the frequency range over which the output decreases by 3 dB. | + | ;Bandwith: The most common definition for the Bandwidth of this circuit is the frequency range over which the output decreases by 3 dB. |

| + | |||

| + | ;Decibels | ||

| + | :The decibel system is a logarithmic scale for the ratio of two quantities | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;For power | ||

| + | :dB = <math>10 \log_{10} \left ( \frac{P_{in}}{P_{out}}\right )</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ;For amplitude (Voltage) | ||

| + | :dB = <math>20 \log_{10} \left ( \frac{V_{in}}{V_{out}}\right )</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A 3dB drop corresponds to the frequency at which the circuits power is cut in half from the resonance frequency. | ||

:<math>P = I^2 R</math> | :<math>P = I^2 R</math> | ||

| Line 585: | Line 604: | ||

:The Band Width is a measurement of the two frequencies which will decrease the resonance voltage by 30 %. | :The Band Width is a measurement of the two frequencies which will decrease the resonance voltage by 30 %. | ||

| − | [[File:TF_EIM_BandWidthDef_LC.gif | | + | [[File:TF_EIM_BandWidthDef_LC.gif | 400 px]] |

;Quality Factor | ;Quality Factor | ||

| Line 662: | Line 681: | ||

:<math>\left | \frac{V_{out}}{V_{in}}\right | =\frac{R}{R+R_L}</math> | :<math>\left | \frac{V_{out}}{V_{in}}\right | =\frac{R}{R+R_L}</math> | ||

| + | [[File:TF_EIM_RLC.png | 200 px]] | ||

=== Phase shift=== | === Phase shift=== | ||

Latest revision as of 16:51, 5 February 2015

Alternating Current (AC)

Thus far we have discussed direct current circuits which were built from a battery (constant voltage supply).

Another type of circuit is one in which the current is driven in an alternating fashion. Typically the current is increased to some positive maximum value, then decreased until it passes through zero and reverses direction until it reaches another maximum value and then it is decreased again, passing though zero once more on its way to a positive maximum value.

Definitions

- frequency (, )

- The frequency is number of complete cycles which occur in 1 sec (cycles/sec = Hz)

- Angular frequency = = radians/sec

- Period

- The period is the time to complete one cycle = 1/

- Amplitude

- The change in the current from zero to its most positive value

- peak-to-peak

- The amount the current changes from its largest positive value to its most negative.

- phase

- The time a current takes to reaches its maximum value compared to another alternating current

- Note

- The above definitions can be used for voltage as easily as current.

Mathematical description

Trigonometric

- Note

- A 180 degree ( radian) phase shift will put the above cosine wave completely out of sync with the original one such that if we add the two signals together the net current would be zero.

I_{RMS}

With this functional form for the alternating current we can now calculate another property, the RMS or root mean square.

The RMS quantifies an average fluctuation of the alternating current such that

where T represent the time interval over which the average is calculated ()

- if T is infinite or an integer number of cycles

Power

The instantaneous power dissipated in a resister by an alternating current is given as

Average power

Current using Complex notation

Another mathematical expression for an alternating current uses complex variables

Expressing the current in this form will be useful later

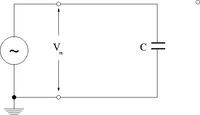

Voltage sources of AC current

The circuit symbol for an emf used to drive alternating currents is given below

A mathematical form is for an AC voltage source is:

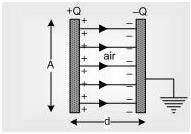

Capacitors

A capacitor is a device used to store charge in a circuit. The simplest capacitor is built from two conducting plates placed close to each other.

- Notice

- The potential is constant over the face of the capacitor

The symbol for a capacitor in a circuit is usually.

or

electrolytic symbol

The electrolytic capacitor

Electrolytic capacitors can be shorted out. Put the positive probe from the voltmeter on the positive side of the electrolytic capacitor, the capacitor should be good if you measure a large resistance otherwise a shorted electrolytic capacitor (small resistance) is a bad one.

Capacitor Properties

- Measures ability to store charge

- : Double Q Doubles V

- SI units = Farrads = Coul/Volt

- Magnitude depends on the elements geometry (conductor area, separation of conductors, ...)

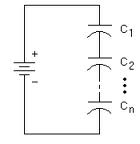

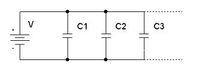

Capacitors in Parallel and Series

Series

Capacitors in Series add like resistors in Parallel.(Capacitance decreases when hooked up in series)

- Note

- The same amount of charge is pushed onto each capacitor

For capacitors in series you can apply the loop theorem for the above case and the one where all the capacitors are replaced by a single capacitor.

Parallel

Capacitors in parallel add like resistors in Series (Capacitance increases when hooked up in parallel)

If you were to replace all capacitors with an equivalent capacitance (C_{eq}) then the charge driven onto the equivalent capacitance would be equal to the sum of the charge driven onto each capacitor.

- ...

- ...

- ...

Charging/Discharging Capacitor circuit

If

then applying loop theorem lead to

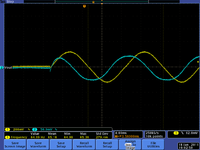

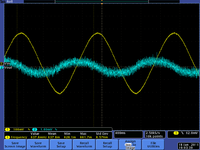

- Notice that the current is 90 degrees out of phase with the driving voltage.

- Note

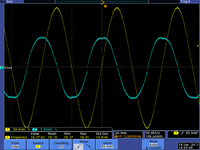

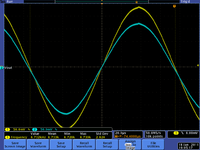

- The current increases faster than the voltage. Below are a few scope pictures measuring the voltage coming out of the voltage source and the voltage on the ground side of the capacitor (the capacitor is grounded through the scope). This is actually a high pass filter because of the internal resistance of the scope used to measure .

| 1 Hz | 16Hz | kHz |

Reactance: Resistive nature of capacitance

To illustrate the resistive nature of capacitors, let's write the driving voltage in using complex notation

The notation

- : Euler's equation

- The real part of a complex variable.

The current is written as

- (The current is 90 degrees out of phase with the voltage)

where

- Effective impedance of a Capacitor

- Observe

- At high frequencies the effective impedance (X_C) is small so the driving voltage should pass right through.

- At low frequencies the effective impedance (X_C) is large so the driving voltage will be severely attenuated.

- Capacitors block Alternating Currents so you can reduce ripples on DC voltages.

- You could measure the capacitance by measuring for several frequencies

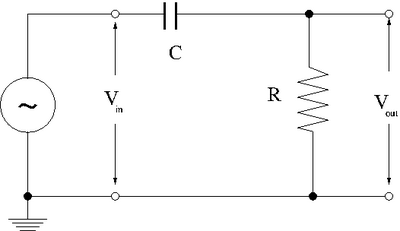

RC circuit

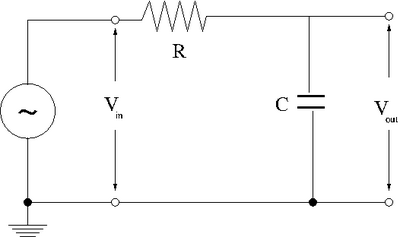

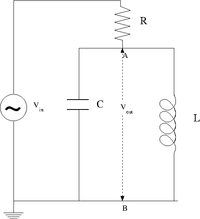

The Low pass Fiter

Now add a resistor in series with the capacitor in the above capacitor charging circuit so it resembles the circuit below

Quick Solution

Applying the loop theorem using the reactance of the capacitor instead of Q/C

- the capacitor can be added in series with the other resistor

It looks like the voltage divider from the resistance section

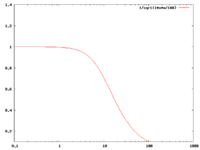

To evaluate where and

Let

- break point (cut off ) frequency

then

- Note

- The RC circuit is another way to measure the capacitance by measureing -vs- and do a linear extrapolation to determine the break point frequency.

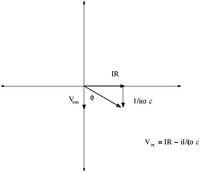

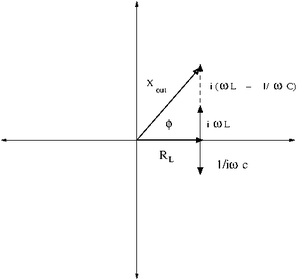

Phasor Diagram

Phasor diagrams are a technique used to illustrate the phase difference between the input and output alternating voltages/currents.

Returning to the loop theorem for the low pass RC filter

We can write the voltage as a complex variable using a coordinate system in which the "x-axis" represents real numbers and the "y-axis" represents the complex components. This is analogous to expressing 2-D vectors.

Below is a figure representing the complex plane.

The angle is the angle between and Based on the above Phasor diagram

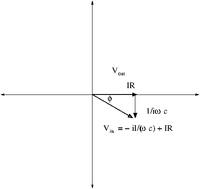

High Pass Filter

A high pass filter switches the order of the resistor and the capacitor.

Using the same reactance based analysis as above

- Phasor diagram

The phasor diagram is very similar except this time V_{out} is along the x-axis

Returning to the loop theorem for the low pass RC filter

We can write the voltage as a complex variable using a coordinate system in which the "x-axis" represents real numbers and the "y-axis" represents the complex components. This is analogous to expressing 2-D vectors.

Below is a figure representing the complex plane.

The angle is the angle between and Based on the above Phasor diagram

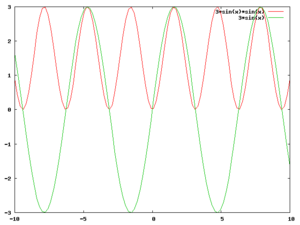

High Pass -vs- Low Pass graphs

if

Then

| Low pass | High Pass |

exact solution

Again apply the loop theorem

or

- First order non-homogeneous linear differential equation

First solve homogeneous part

- First order homogeneous linear differential equation

The above is integratable

This gives you the general solution for the homogeneous problem

In this case it represents the solution for a discharging capacitor.

Trial solution method for Non-Homogeneous Solution

A common and more general technique to solving such a differential equation is to use the solution from the discharging equation (the homogeneous diff. eq.) as a trial solution to the charging (non-homogeneous) problem by constructing the linear combination below.

Where A & B are constants to e determined

You then substitute this trial solution into the differential equation and apply boundary conditions to determine the coefficients.

To determine the other coefficient you apply the boundary condition that q = 0 when t=0

Inductance

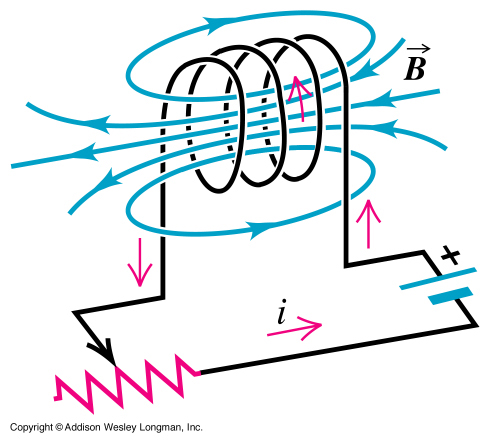

Inductor/Choke

An inductor is basically a loop of wire wrapped around a core (or air) to form a coil.

Consider what happens in the above circuit when you first connect a voltage source (or close the switch).

1.) A current starts to flow through the wire such that I=V/R (R can be the internal resistance of the battery which changes with time).

2.) A current produces a magnetic field

- Ampere's Law

If the current distribution isn't symmetric enough to make the line integral easy

then you may need to use

- Biot-Savart Law

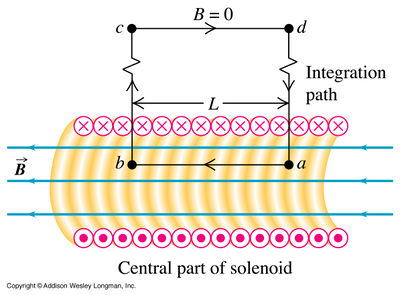

Most inductors take the geometrical form of a solenoid.

- = total current enclosed by the loop is I times the number of loops N

where

- number of turns per unit length

3.) When using an AC source the current is changing with time and as a result the B-field is also changing in time

4.) The changing current induces and emf ()

Faraday's law of induction says

- = self induced emf

where

- : There are 3 ways to induce an emf (B and A change with time or the angle between them)

The B-field is usually perpendicular to the area of the induction and mostly uniform.

The above is the emf induced in a single loop

- If you assume there are N loop in the inductor

- Then

- = Inductance

where

- length of loop

- radius of coil

Lenz's law says that the induced current will appear in a direction that opposes the change producing it.

So in essence the inductor acts "like" a resistor which resists the current flow according to the amount of current is changing.

There is an effective reactance for inductors as there was one for capacitors

Inductor Reactance

Consider an AC voltage source with an inductor attached.

Loop theorem

Assume I(0) =0 and rewrite in terms of a phase shifted

- : V and I are 90 degrees out of phase

- Note

- Large L makes it hard to change current

- Small L makes it easy to change current

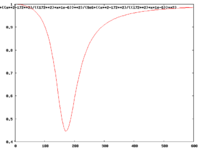

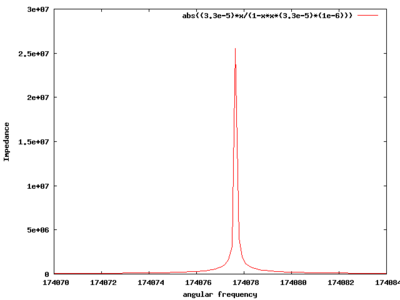

parallel LC circuit (Band Stop/Notch Filter/ tank circuit)

The above circuit has a resistor in series with an inductor and capacitor in parallel.

Using the complex analysis techniques for AC circuits you can consider the Inductor and Capacitor as impedances in parallel.

so

or

| and |

|

| rad/s |

Phase differences

- Notice

- &

The current through the inductor side of the circuit is 180 degrees out of phase with the capacitor side.

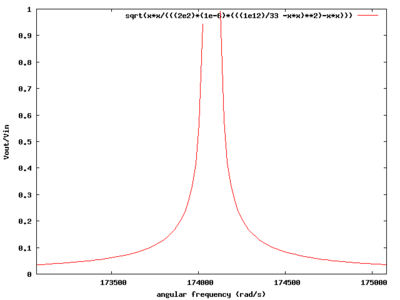

gain

Loop Theorem

or

- Notice

- When then the AC signal is attenuated.

Looking at the Voltage divider aspect of the circuit

| and and R=200 |

|

| rad/s or Hz |

Q and Bandwidth

In the above circuit

The inductors reactance at this resonance frequency is

- Bandwith

- The most common definition for the Bandwidth of this circuit is the frequency range over which the output decreases by 3 dB.

- Decibels

- The decibel system is a logarithmic scale for the ratio of two quantities

- For power

- dB =

- For amplitude (Voltage)

- dB =

A 3dB drop corresponds to the frequency at which the circuits power is cut in half from the resonance frequency.

- The Band Width is a measurement of the two frequencies which will decrease the resonance voltage by 30 %.

- Quality Factor

- The Quality factor for this circuit may be expressed in term of the bandwidth such that

- Notice

- The Bandwidth can be changed in the above circuit by changing the step down resistor (R) without changing the resonance frequency.

Quality Factor (Q)

The Quality factor of a circuit is defined in terms of a ratio between the energy stored to the energy lost.

- How much energy does an inductor store?

- How much energy does an inductor lose?

The system loses energy through heat via power dissipation so in general

- where R is the effective resistance of the circuit

- Note

- A circuit with high Q will have amplitude (or blocking) at the desired resonance frequency and the least amplitude (or blocking) at non-resonant frequencies.

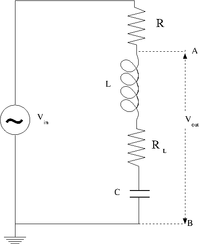

An Inductor in series with a capacitor is known as a Band Pass filter. Since wires are used to hook everything up and real capacitors have leakage resistance so an RLC circuit is a realistic version of the series LC circuit.

RLC circuit

An RLC circuit is a Resistor, an Inductors, and a Capacitor in series with an electromotive force.

Effective impedance

Gain

Loop Theorem

Voltage Divider

Let

Then

When

Then

Phase shift

Voltage lags current for a capacitor

Voltage leads current for Inductor

If then the phase shift is negative

If then the phase shift is positive