Difference between revisions of "Simulations of Particle Interactions with Matter"

| Line 768: | Line 768: | ||

:<math>(p^{\; \prime \prime}c)^2 = (pc)^2 - 2E_k\sqrt{(pc)^2 +Mc^2)^2} + E_k^2</math> : cons of E | :<math>(p^{\; \prime \prime}c)^2 = (pc)^2 - 2E_k\sqrt{(pc)^2 +Mc^2)^2} + E_k^2</math> : cons of E | ||

| − | :<math>= (pc)^2 + E_k^2 + 2E_km_ec^2 -2pc\sqrt{E_k^2+2E_km_ec^2} \cos{\ | + | :<math>= (pc)^2 + E_k^2 + 2E_km_ec^2 -2pc\sqrt{E_k^2+2E_km_ec^2} \cos(\theta)</math> : cons of P |

| + | |||

| + | \Rightarrow | ||

| + | |||

| + | : <math>pc \cos(\theta) \sqrt{1+\frac{2m_ec^2}{E_k}} = \sqrt{(pc)^2+(Mc^2)^2} + m_ec^2</math> | ||

=== Range Straggling=== | === Range Straggling=== | ||

Revision as of 21:03, 20 September 2007

Overview

Particle Detection

A device detects a particle only after the particle transfers energy to the device.

Energy intrinsic to a device depends on the material used in a device

Some device of material with an average atomic number () is at some temperature (). The materials atoms are in constant thermal motion (unless T = zero degrees Klevin).

Statistical Thermodynamics tells us that the canonical energy distribution of the atoms is given by the Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics such that

represents the probability of any atom in the system having an energy where

Note: You may be more familiar with the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution in the form

where would represent the molesules in the gas sample with speeds between and

Example 1: P(E=5 eV)

- What is the probability that an atom in a 12.011 gram block of carbon would have and energy of 5 eV?

First lets check that the probability distribution is Normailized; ie: does ?

is calculated by integrating P(E) over some energy interval ( ie:). I will arbitrarily choose 4.9 eV to 5.1 eV as a starting point.

assuming a room empterature of

then

and

or in other words the precise mathematical calculation of the probability may be approximated by just using the distribution function alone

This approximation breaks down as

Since we have 12.011 grams of carbon and 1 mole of carbon = 12.011 g = carbon atoms

We do not expect to see a 5 eV carbon atom in a sample size of carbon atoms when the probability of observing such an atom is

The energy we expect to see would be calculated by

If you used this block of carbon as a detector you would easily notice an event in which a carbon atom absorbed 5 eV of energy as compared to the energy of a typical atom in the carbon block.

- Silicon detectors and Ionization chambers are two commonly used devices for detecting radiation.

approximately 1 eV of energy is all that you need to create an electron-ion pair in Silicon

approximately 10 eV of energy is needed to ionize an atom in a gas chamber

The low probability of having an atom with 10 eV of energy means that an ionization chamber would have a better Signal to Noise ratio (SNR) for detecting 10 eV radiation than a silicon detector

But if you cool the silicon detector to 200 degrees Kelvin (200 K) then

So cooling your detector will slow the atoms down making it more noticable when one of the atoms absorbs energy.

also, if the radiation flux is large, more electron-hole pairs are created and you get a more noticeable signal.

Unfortunately, with some detectore, like silicon, you can cause radiation damage that diminishes it's quantum efficiency for absorbing energy.

The Monte Carlo method

- Stochastic

- from the greek word "stachos"

- a means of, relating to, or characterized by conjecture and randomness.

A stochastic process is one whose behavior is non-deterministic in that the next state of the process is partially determined.

Quantun Mechanics is perhaps the best example such a non-deterministic systems. The canonical systems in Thermodynamics is another example.

Basically the monte-carlo method uses a random number generator (RNG) to generate a distribution (gaussian, uniform, Poission,...) which is used to solve a stochastic process based on an astochastic description.

Example 2 Calculation of

- Astochastic description

- may be measured as the ratio of the area of a circle of radius divided by the area of a square of length

You can measure the value of if you physically measure the above ratios.

- Stochastic description

- Construct a dart board representing the above geometry, throw several darts at it, and look at a ratio of the number of darts in the circle to the total number of darts thrown (assuming you always hit the dart board).

- Monte-Carlo Method

- Here is an outline of a program to calulate using the Monte-Carlo method with the above Stochastic description

begin loop x=rnd y=rnd dist=sqrt(x*x+y*y) if dist <= 1.0 then numbCircHits+=1.0 numbSquareHist += 1.0 end loop print PI = 4*numbCircHits/numbSquareHits

A Unix Primer

To get our feet wet using the UNIX operating system, we will try to solve example 2 above using a RNG under UNIX

List of important Commands

- ls

- pwd

- cd

- df

- ssh

- scp

- mkdir

- printenv

- emacs, vi, vim

- make, gcc

- man

- less

- rm

Most of the commands executed within a shell under UNIX have command line arguments (switches) which tell the command to print information about using the command to the screen. The common forms of these switches are "-h", "--h", or "--help"

ls --help ssh -h

the switch deponds on your flavor of UNIX

if using the switch doesn;t help you can try the "man" (sort for manual) pages (if they were installed). Try

man -k pwd

the above command will search the manual for the key word "pwd"

Example 3: using UNIX

Step

- login to inca.

click here for a description of logging in if using windows - mkdir src

- cd src

- cp -R ~tforest/NucSim/Day1 ./

- ls

- cd Day1

- make

- ./rndtest

Here is a web link to the source files you can copy in case the above doesn't work

A Root Primer

Example 1: Create Ntuple and Draw Histogram

Cross Sections

Definitions

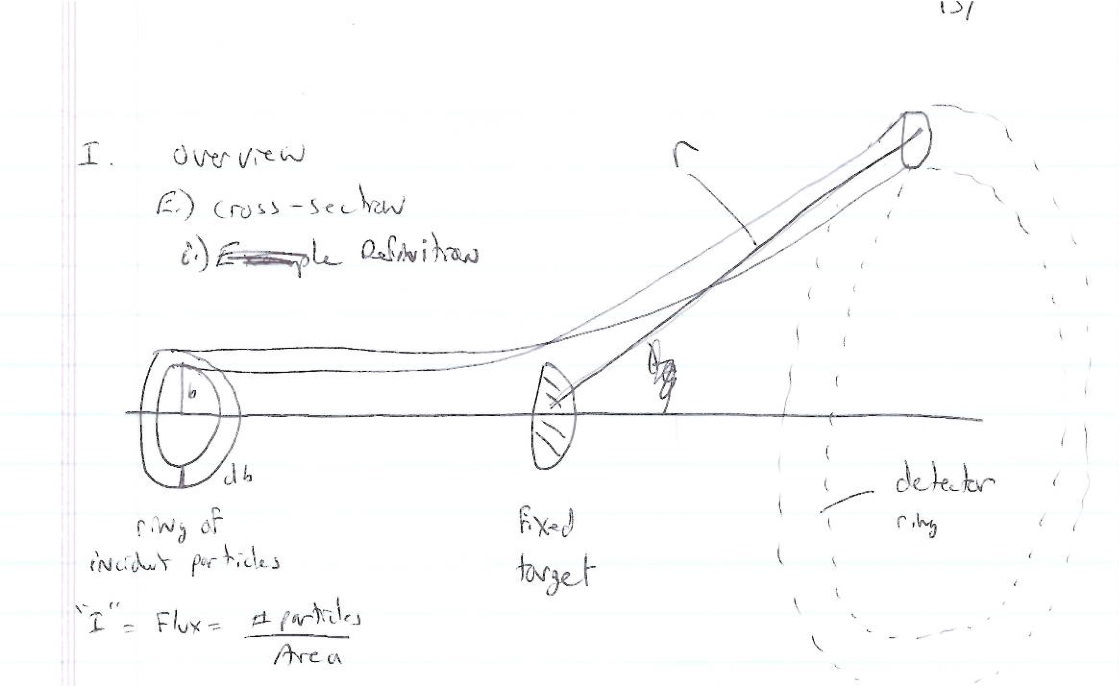

- Total cross section

- =

- Differential cross section

- =

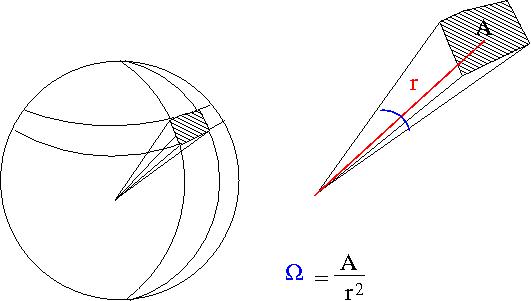

- Solid Angle

- = surface area of a sphere covered by the detector

- ie;the detectors area projected onto the surface of a sphere

- A= surface area of detector

- r=distance from interaction point to detector

- sterradians

- if your detector was a hollow ball

- sterradians

- Units

- Cross-sections have the units of Area

- 1 barn =

- [units of ] =

- Fixed target scattering

- = # of particles in =

- is the area of the ring of incident particles

- = # particles in a ring of radius and thickness

You can measure if you measure the # of particles detected in a known detector solid angle from a known incident particle Flux () as

Alternatively if you have a theory which tells you which you want to test experimentally with a beam of flux then you would measure counts (particles)

- Units

- = # of particles

- or for a count rate divide both sides by time and you get beam current on the RHS

- integrate and you have the total number of counts

- Classical Scattering

- In classical scattering you get the same number of particle out that you put in (no capture, conversion,..)

- tells you how the impact parameter changes with scattering angle

Example 4: Elastic Scattering

This example is an example of classical scattering.

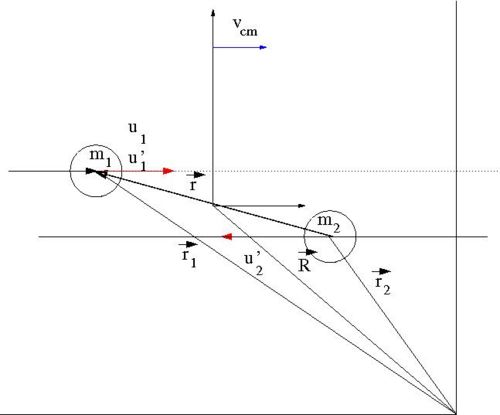

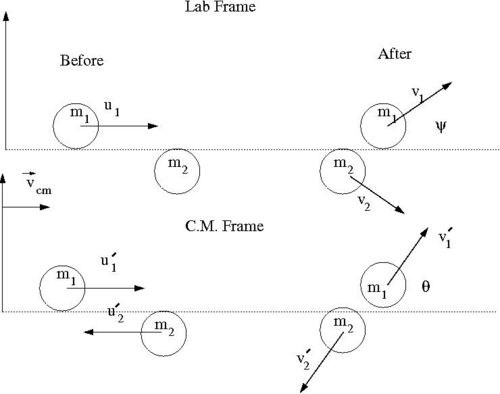

Our goal is to find for an elastic collision of 2 impenetrable spheres of diameter . To solve this elastic scattering problem we will describe the collision using the Center of Mas (C.M.) coordinate system in terms of the reduced mass. As we shall see, by using C.M. coordinate system the 2-body collision becomes a 1-body problem. Then we will describe the motion of the reduced mass in the C.M. Frame.

Media:SPIM_ElasCollis_Lab_CM_Frame.xfig.txt

Media:SPIM_ElasCollis_Lab_CM_Frame.xfig.txt

- Variable definitions

- = impact parameter ; distance of closest approach

- = mass of incoming ball

- = mass of target ball

- = iniital velocity of incoming ball in Lab Frame

- = final velocity of in Lab Frame

- = scattering angle of in Lab frame after collision

- = iniital velocity of in C.M. Frame

- = final velocity of in C.M. Frame

- = iniital velocity of in C.M. Frame

- = final velocity of in C.M. Frame

- = scattering angle of in C.M. frame after collision

- Determining the reduced mass

- vector definitions

- = a position vector pointing to the location of

- = a position vector pointing to the location of

- = a position vector pointing to the center of mass of the two ball system

- = the magnitude of this vector is the distance between the two masses

In the C.M. reference frame the above vectors have the following relationships

solving the above equations for and and defining the reduced mass as

- reduced mass

leads to

We can use the above reduced mass relationships to construct the Lagrangian in terms of instead of and thereby reducing the problem from a 2-body problem to a 1-body problem.

- Construct the Lagrangian

The Lagrangian is defined as:

where

kinetic energy of the system

Potential energy of the system which describes the interaction

- =

after substituting derivative of the expressions for and

- = The 2-body problem is now described by a 1-body Lagrangian

Lagranges equations of motion are given by

where represents on of the coordinate (cannonical variables).

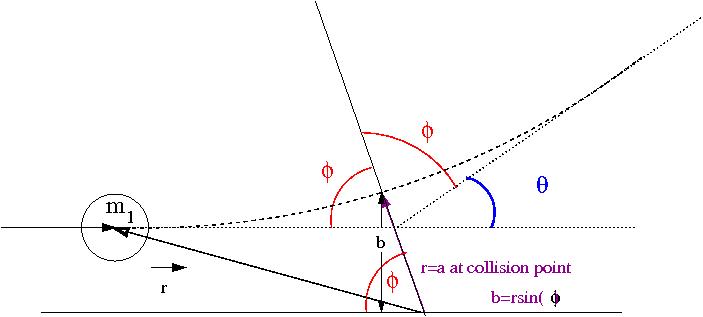

To get the classical scattering cross section we are interested in finding an expression for the dependence of the impact parameter on the scattering angle,.

Now lets redraw the collision in terms of a reference frame fixed on (before collision its the Lab Frame but not after collision).

Media:SPIM_ElasColls_CMFrame_xfig.txt

Media:SPIM_ElasColls_CMFrame_xfig.txt

The C.M. Frame rides along the center of mass, the above coordinate system though has its origin on and only overlaps in space with the CM frame at the collision point sufficiently to illustrate . If then there is no collision (), otherwise a collision happens when r=a (the distance between the balls is equal to their diameter). A head on collision is defined as ().

- Observation

- as gets smaller, gets bigger

Using plane polar coordinates () we can describe the problem in the lab frame as:

Lagranges Equation of Motion:

there is a constant of motion ( Constant angular momentum)

substitute into

The two equations above are in terms of and whereas our goal is to find an expression for . Since is related to and is related to (; see figure above) we should try and find expressions for in terms of

- Trick

- or

We now need an expression for in order to integrate the above equation to determine the functional dependence of and hence.

Since Energy is conserved (Elastic Scattering), we may define the Hamiltonian as

solving for

substituting the above into the equation for and integrating:

For :

substituting this expression for into the last expression for above :

- Integral Table

let

then

or

- Now substitue the above into the expression for

drop the negative sign, sqrt in denominator allows this, and use the trig identity

- compare with result from definition

- = scattering cross-section

- number of particles scattered = number of incident particles

- Area = = The area profile in which a collision occurs

Lab Frame Cross Sections

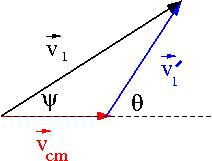

The C.M. frame is often chosen to theoretically calculate cross-sections even though experiments are conducted in the Lab frame. In such cases you will need to transform cross-sections between two frames.

The total cross-section should be frame independent

or

where

is in the CM frame and is in the Lab frame.

- A non-relativistic transformation

The transformation is governed by the dependence of on

Lets return back to our picture of the scattering Process

if we superimpose the vectors and we have

Trig identities (non-relativistic Gallilean transformation) tell us

solving for

For an elastic collision only the directions change in the CM Frame: &

- From the definition of the C.M.

- conservation of momentum in CM Frame

- Gallilean Coordinate transformation

- another experission for

using the above gallilean transformation we can do the following

or

after a little trig substitution

constant

now use the chain rule to find

- constant

after substitution:

For the above equation to be more useful one would prefer to recast it in terms of only and masses.

Stopping Power

Ann. Phys. vol. 5, 325, (1930)

Bethe Equation

Classical Energy Loss

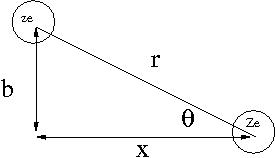

Consider the energy lost when a particle of charge () traveling at speed is scattered by a target of charge (). Assume only the coulomb force causes the particle to scatter from the target as shown below.

- Notice

- as is scattered the horizontal component of the coulomb force () flips direction; ie no horizontal force

where

- k =

- r = distance between incident projectile and target atom

- b= impact parameter of collision

Using the definition of Impulse one can determine the momentum change of as

Let's assume that the energy lost by the incident particle is absorbed by an electron in the target atom. This energy may be cast in terms of the incident particles momentum change as

By calculating the change in momentum () of the incident particle we can infer the amount of energy lost by the incident particle and absorbed one of the target materials atomic electrons.

using we have

casting this in terms of the classical atomic electron radius

- just equate

Then

and

- : = 1 here because I shall assume the energy is lost to just the electron and the Atom is a spectator

Now let's calculate an expression representing the average energy lost for an incident particle traversing a material of some thickness.

Let

- = Probability of an interaction taking place which results in an energy loss

If we let

Z = Atomic Number = # electrons in target Atom = number of protons in an Atom

N = Avagadros number =

A = Atomic mass =

= probability of hitting an atomic electron in the area of an annulus of radius () with an energy transfer between and

Then

- = energy lost by the incident particle per distance traversed through the material

I am just adding up all the energy losses weighted by the probability of the energy loss to find the total energy loss.

- : classically

- =

- =

- =

where if A=1

The limits of the above integral should be more physical in order to reflect the limits of the physics interaction. Let b_{min} and b_{max} represent the minimum and maximum possible impact parameter where the physics is discribed, as shown above, by the coulomb force.

- What is ?

if then diverges and the energy transfer . Physically there is a maximum energy that may be transferred before the physics of the problem changes (ie: nuclear excitation, jet production, ...). The de Borglie wavelength of the atom is used to estimate a value for such that

- What is b_{max}?

As gets bigger the interaction is "softer" and longer. If the interaction time () is so long that it is equivalent to an electron orbit () then the atom looks more like it is neutrally charged. You move from an interaction in which the electron orbit is perturbed adiabatically such that there is no orbit change and the minimum amount of energy is transferred to no interaction taking place because the atom is neutral.

Let

- : fields at high velocities get Lorentz contracted

- : I mean excitation energy of target material ( )

Condition for :

Example 5: Find for a 10 MeV proton hitting a liquid hydrogen () target

A = Z=z=1

= 0.511 MeV

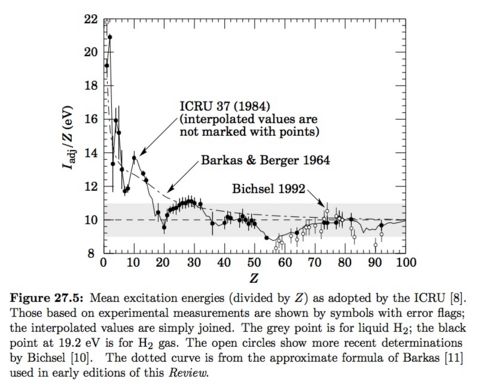

I = 21.6 eV : see solid data point From Figure 27.5 on pg 6 of PDG below.

Just need to know and

"a 10 MeV proton" Kinetic Energy (K.E.) = 10 MeV =

Proton is not relativistic

Plugging in the numbers:

- How much energy is lost after 0.3 cm?

= 0.07

- = 2.2 MeV

Bethe-Bloch Equation

While the classical equation above works in a limited kinematic regime, the Bethe-Bloch equation includes the corrections needed to cover most kinematic regimes for heavy particle energy loss.

where

- = Max K.E. transferable to the Target of mass in a single collision.

- = correction for electron spin and very distant collisions which deform the electron atomic orbits each process reducing dE/dx by

- = density correction term: in the classical derivation the material is treated as just a system of atoms uniformly distributed in space. These Atoms, however, give the material polarizability which can reduce the electric field (dielectric).

GEANT 4 implementation

The GEANT4 file (version 4.8.p01)

source/processes/electromagnetic/standard/src/G4BetheBlockModel.cc

is used to calculate hadron energy loss.

line 132

where

line 143

- = density corection =

line 148

- = shell correction, corrects for the classical asumption that the atomic electron velicity is initially zero; or the the incident particles velocity is far greater than the atomic electron's velocity.

line 154

Energy Dependence

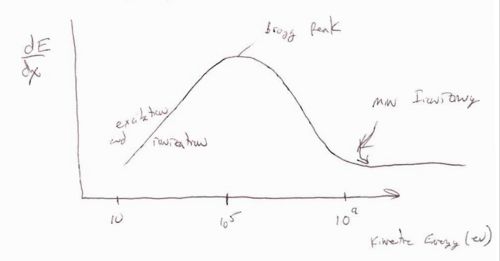

The above curve shows the energy loss per disntace traveled () as a function of the incident particles energy. There are three basic regions. At low incident energies ( < 10^5 eV) the incident particle tends to excite or even ionize the atoms in the material it is penetrating. The maximum amount of energy loss per distance traveled is defined at as the Bragg peak. The region after the Bragg peak in which the energy loss per distance traveled reaches its smalest value is reffered to as the point of minimum ionizing. Minimimum ionizing particles will have incident energies corresponding to this value or larger. The characteristic of the minimum ionizing particles is that their energy loss per distance traveled is essentially constant making simulations easier until the drop below the minimum ionizing energy level as they are passing through the material.

In general the Bethe-Bloch equation breaks down at low energies (below the Bragg peak) and is a good description (to within 10%) for

- and < 26 (Iron)

the term in the Bethe-Bloch equation dominates between the Bragg peak and the minimum ionization region.

the term and its corrections influence the dependence of as you move up in energy beyond the minimum ionization point.

Energy Straggling

While the Bethe-Bloch formula gives you a way to quantify the amount of energy a heavy charged particle looses as a function of the distance traveled, you should realize that when you calculate the total energy lost via

you are only determining the AVERAGE energy loss. In other words, Bethe-Bloch is the Astochastic process describing energy loss.

In reality the energy loss process is a stochastic process because of the statistical fluctuations which occur in the actual number of collisions which take place.

Thick Absorber

A thick absorber is one in which a large number of collisions takes place. In this situation the central limit theorem from statistics tells you that the larger number of random variables involved will result in observables which are distributed in a Gaussian manner.

The gaussian probability function is defined as

where the Full Width at Half Max (FWHM) of the distribution =

In the case of energy loss, the variance using the Bethe-Bloch equation should be

the realitivistic variance is

for very thick absorbers see

C. Tschaler, NIM 64, (1968) 237 ; ibid, 61, (1968) 141

When simulating energy loss of heavy charged particles the Bethe-Bloch equation may be used to calculate a \frac{dE}{dx} which can determine the average energy loss at the given kinetic energy of the particle. This average is then smeared according to a gaussian distribution of variance

Thin Absorbers

In thin absorbers the number of collisions is small preventing the use of the central limit theorem to describe the stochatic process of energy loss in terms of a Gaussian distribution. The Large energy transfers that are possible cause the energy loss distribution to look like a Gaussian one with a high energy tail (or foot).

The skewness of the resulting energy loss distribution is quantified as

- = lead term in Bethe Bloch equation

= density of absorbing material.

- = max energy transfered in 1 collision (headon / knock out collision)

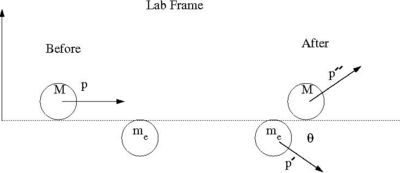

This comes from the relativistic kinematics of an Elastic Collisions.

Conservation of Momentum :

Conservation of Energy :

using conservation of E & P as well as substituting for you can show

this will lead to the equation

- : cons of E

- : cons of P

\Rightarrow