Newton's Laws of Motion

Limits of Classical Mechanic

Classical Mechanics is the formulations of physics developed by Newton (1642-1727), Lagrange(1736-1813), and Hamilton(1805-1865).

It may be used to describe the motion of objects which are not moving at high speeds (0.1[math] c[/math]) nor are microscopically small ( [math]10^{-9} m[/math]).

The laws are formulated in terms of space, time, mass, and force:

Space and Time

Space

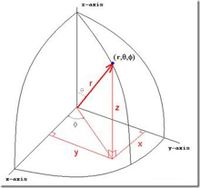

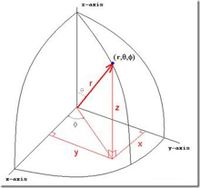

Cartesian, Spherical, and Cylindrical coordinate systems are commonly used to describe three-dimensional space.

Cartesian

Vector Notation convention:

Position:

- [math]\vec{r} = x \hat{i} + y \hat{j} + z \hat{k} = (x,y,z) = \sum_1^3 r_i \hat{e}_i[/math]

Velocity:

- [math]\vec{v}[/math] = [math]\frac{d \vec{r}}{dt}[/math] = [math]\frac{d x}{dt}\hat{i} + x\frac{d \hat{i}}{dt} + \cdots[/math]

cartesian unit vectors do not change with time (unit vectors for other coordinate system types do)

- [math]\frac{d \hat{i}}{dt} =0 =\frac{d \hat{j}}{dt} =\frac{d \hat{k}}{dt}[/math]

- [math]\vec{v}[/math] = [math]\frac{d \vec{r}}{dt}[/math] = [math]\frac{d x}{dt}\hat{i} + \frac{d y}{dt}\hat{j} + \frac{d z}{dt}\hat{k} [/math]

Similarly Acceleration is given by

- [math]\vec{a}[/math] = [math]\frac{d \vec{v}}{dt}[/math] = [math]\frac{d^2 x}{dt^2}\hat{i} + \frac{d^2 y}{dt^2}\hat{j} + \frac{d^2 z}{dt^2}\hat{k} [/math]

Polar

Vector Notation convention:

Vector Notation convention:

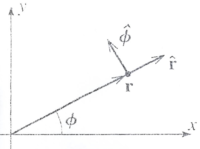

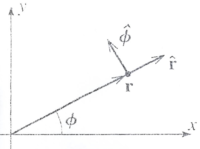

Position:

Because [math]\hat{r}[/math] points in a unique direction given by [math]\hat{r} = \frac{\vec{r}}{|r|}[/math] we can write the position vector as

- [math]\vec{r} = r \hat{r}[/math]

- [math]\vec{r} \ne r \hat{r} +\phi \hat{\phi} [/math]: [math]\phi[/math] does not have the units of length

The unit vectors ([math]\hat{r}[/math] and [math]\hat{\phi}[/math] ) are changing in time. You could express the position vector in terms of the cartesian unit vectors in order to avoid this

- [math]\vec{r} = r \cos(\phi) \hat{i} + r \sin(\phi)\hat{j}[/math]

The dependence of position with [math]\phi[/math] can be seen if you look at how the position changes with time.

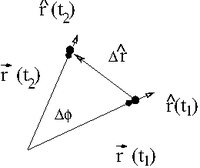

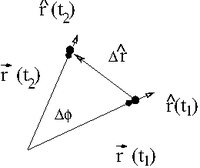

Consider the motion of a particle in a circle. At time [math]t_1[/math] the particle is at [math]\vec{r}(t_1)[/math] and at time [math]t_2[/math] the particle is at [math]\vec{r}(t_2)[/math]

If we take the limit [math]t_2 \rightarrow t_1[/math] ( or [math]\Delta t \rightarrow 0[/math]) then we can write the velocity of this particle traveling in a circle as

- [math]\hat{r} (t_2)-\hat{r}(t_1) \equiv \Delta \hat{r} = \Delta \phi \hat{\phi}[/math]

- or

- [math]\frac{ d \hat{r}}{t} = \frac{d \phi}{dt} \hat{\phi}[/math]

Thus for circular motion at a constraint radius we get the familiar expression

- [math]\vec{v} = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0} \frac{\vec{r}(t_2)-\vec{r}(t_1)}{\Delta t}= \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0} \frac{r\left( \hat{r}(t_2) - \hat{r}(t_1)\right)}{\Delta t} = r \frac{\Delta \phi}{\Delta t} \hat{\phi} = r \omega \hat{\phi}[/math]

- [math]\vec{v} = r \frac{d \phi}{dt} \hat{\phi}[/math]

If the particle is not constrained to circular motion ( i.e.: [math]r[/math] can change with time) then the velocity vector in polar coordinates is

Velocity:

- [math]\vec{v}[/math] = [math]\frac{d \vec{r}}{dt}\hat{r} + r\frac{d \phi}{dt} \hat{\phi}[/math]

- or in more compact form

- [math]\vec{v}=\vec{\dot{r}} = \dot{r} \hat{r} + r \dot{\phi} \hat{\phi}= v_r \hat{r} + v_{\phi} \hat{\phi}[/math]

cartesian unit vectors do not change with time (unit vectors for other coordinate system types do)

- [math]\frac{d \hat{i}}{dt} =0 =\frac{d \hat{j}}{dt} =\frac{d \hat{k}}{dt}[/math]

- [math]\vec{v}[/math] = [math]\frac{d \vec{r}}{dt}[/math] = [math]\frac{d x}{dt}\hat{i} + \frac{d y}{dt}\hat{i} + \frac{d z}{dt}\hat{i} [/math]

Cylindrical

Spherical

Vectors

Scaler ( Dot ) product

Vector ( Cross ) product

Forest_Ugrad_ClassicalMechanics