Difference between revisions of "Forest NucPhys I"

| Line 1,047: | Line 1,047: | ||

:<math>\psi_i(\vec{r}) = e^{i \vec{k}_i \cdot \vec{r}}</math> | :<math>\psi_i(\vec{r}) = e^{i \vec{k}_i \cdot \vec{r}}</math> | ||

:<math>\psi_f^{*}(\vec{r}) = e^{-i \vec{k}_f \cdot \vec{r}}</math> | :<math>\psi_f^{*}(\vec{r}) = e^{-i \vec{k}_f \cdot \vec{r}}</math> | ||

| − | :<math>H_{int} = \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{Q}{|\vec{r}- \vec{R}|}</math> | + | :<math>H_{int} = \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{Q}{|\vec{r}- \vec{R}|} \approx ze^2 \int \int e^{i \vec{q} \cdot \vec{r}} \frac{\rho(\vec{R}}{|\vec{r} - \vec{R}|} dV \dV^{\prime}</math> |

==Mass and Binding Energy == | ==Mass and Binding Energy == | ||

Revision as of 05:58, 25 February 2008

Advanced Nuclear Physics

References:

Krane:

Catalog Description:

PHYS 609 Advanced Nuclear Physics 3 credits. Nucleon-nucleon interaction, bulk nuclear structure, microscopic models of nuclear structure, collective models of nuclear structure, nuclear decays and reactions, electromagnetic interactions, weak interactions, strong interactions, nucleon structure, nuclear applications, current topics in nuclear physics. PREREQ: PHYS 624 OR PERMISSION OF INSTRUCTOR.

PHYS 624-625 Quantum Mechanics 3 credits. Schrodinger wave equation, stationary state solution; operators and matrices; perturbation theory, non-degenerate and degenerate cases; WKB approximation, non-harmonic oscillator, etc.; collision problems. Born approximation, method of partial waves. PHYS 624 is a PREREQ for 625. PREREQ: PHYS g561-g562, PHYS 621 OR PERMISSION OF INSTRUCTOR.

NucPhys_I_Syllabus

Introduction

The interaction of charged particles (electrons and positrons) by the exchange of photons is described by a fundamental theory known as Quantum ElectroDynamics. QED has perturbative solutions which are limited in accuracy only by the order of the perturbation you have expanded to. As a result the theory is quite useful in describing the interactions of electrons that are prevalent in Atomic physics.

Nuclear physics, however, encompasses the physics of describing not only the nucleus of an Atom but also the composition of the nucleons (protons and neutrons) which are the constituent of the nucleus. Quantum ChromoDynamic (QCD) is the fundamental theory designed to describe the interactions of the quarks and gluons inside a nucleon. Unfortunately, QCD does not have a complete solution at this time. At very high energies, QCD can be solved perturbatively. This is an energy at which the strong coupling constant is less than unity where

The "Standard Model" in physics is the grouping of QCD with Quantum ElectroWeak theory. Quantum ElectroWeak theory is the combination of Quantum ElectroDynamics with the weak force; the exchange of photons, W-, and Z-bosons.

The objectives in this class will be to discuss the basic aspects of the nuclear phenomenological models used to describe the nucleus of an atom in the absence of a QCD solution.

Nomenclature

| Variable | Definition |

| Z | Atomic Number = number of protons in an atom |

| A | Atomic Mass |

| N | number of neutrons in an atom = A-Z |

| Nuclide | A specific nuclear species |

| Isotope | Nuclides with same Z but different N |

| Isotones | Nuclides with same N but different Z |

| Isobars | Nuclides with same A |

| Nuclide | A specific nuclear species |

| Nucelons | Either a neutron or a proton |

| J | Nuclear Angular Momentum |

| angular momentum quantum number | |

| s | instrinsic angular momentum (spin) |

| total angular momentum = | |

| Spherical Harmonics, = angular momentum quantum number, = projection of on the axis of quantization | |

| Planks constant/2 |

Notation

= An atom identified by the Chemical symbol with protons and neutrons.

Notice that and are redundant since can be identified by the chemical symbol and can be determined from both and the chemical symbol (N=A-Z).

- example

Historical Review

Rutherford Nuclear Atom (1911)

Rutherford interpreted the experiments done by his graduate students Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden involving scattering of alpha particles by the thin gold-leaf. By focusing on the rare occasion (1/20000) in which the alpha particle was scattered backward, Rutherford argued that most of the atom's mass was contained in a central core we now call the nucleus.

Chadwick discovers neutron (1932)

Prior to 1932, it was believed that a nucleus of Atomic mass was composed of protons and electrons giving the nucleus a net positive charge . There were a few problems with this description of the nucleus

- A very strong force would need to exist which allowed the electrons to overcome the coulomb force such that a bound state could be achieved.

- Electrons spatially confined to the size of the nucleus ( would have a momentum distribution of . Electrons ejected from the nucleus by radioactive decay ( decay) have energies on the order of 1 MeV and not 20.

- Deuteron spin: The total instrinsic angular momentum (spin) of the Deuteron (A=2, Z=1) would be the result of combining two spin 1/2 protons with a spin 1/2 electron. This would predict that the Deuteron was a spin 3/2 or 1/2 nucleus in contradiction with the observed value of 1.

The discovery of the neutron as an electrically neutral particle with a mass 0.1% larger than the proton led to the concept that the nucleus of an atom of atomic mass was composed of protons and neutrons.

Powell discovers pion (1947)

Although Cecil Powell is given credit for the discovery of the pion, Cesar Lattes is perhaps more responsible for its discovery. Powell was the research group head at the time and the tradition of the Nobel committe was to award the prize to the group leader. Cesar Lattes asked Kodak to include more boron in their emulsion plates making them more sensitive to mesons. Lattes also worked with Eugene Gardner to calcualte the pions mass.

Lattes exposed the plates on Mount Chacaltaya in the Bolivian Andes, near the capital La Paz and found ten two-meson decay events in which the secondary particle came to rest in the emulsion. The constant range of around 600 microns of the secondary meson in all cases led Lattes, Occhialini and Powell, in their October 1947 paper in 'Nature ', to postulate a two-body decay of the primary meson, which they called p or pion, to a secondary meson, m or muon, and one neutral particle. Subsequent mass measurements on twenty events gave the pion and muon masses as 260 and 205 times that of the electron respectively, while the lifetime of the pion was estimated to be some 10-8 s. Present-day values are 273.31 and 206.76 electron masses respectively and 2.6 x 10-8 s. The number of mesons coming to rest in the emulsion and causing a disintegration was found to be approximately equal to the number of pions decaying to muons. It was, therefore, postulated that the latter represented the decay of positively-charged pions and the former the nuclear capture of negatively-charged pions. Clearly the pions were the particles postulated by Yukawa.

In the cosmic ray emulsions they saw a negative pion (cosmic ray) get captured by a nucleus and a positive pion (cosmic ray) decay. The two pion types had similar tracks because of their similar masses.

Nuclear Properties

The nucleus of an atom has such properties as spin, mangetic dipole and electric quadrupole moments. Nuclides also have stable and unstable states. Unstable nuclides are characterized by their decay mode and half lives.

Decay Modes

| Mode | Description |

| Alpha decay | An alpha particle (A=4, Z=2) emitted from nucleus |

| Proton emission | A proton ejected from nucleus |

| Neutron emission | A neutron ejected from nucleus |

| Double proton emission | Two protons ejected from nucleus simultaneously |

| Spontaneous fission | Nucleus disintegrates into two or more smaller nuclei and other particles |

| Cluster decay | Nucleus emits a specific type of smaller nucleus (A1, Z1) smaller than, or larger than, an alpha particle |

| Beta-Negative decay | A nucleus emits an electron and an antineutrino |

| Positron emission(a.k.a. Beta-Positive decay) | A nucleus emits a positron and a neutrino |

| Electron capture | A nucleus captures an orbiting electron and emits a neutrino - The daughter nucleus is left in an excited and unstable state |

| Double beta decay | A nucleus emits two electrons and two antineutrinos |

| Double electron capture | A nucleus absorbs two orbital electrons and emits two neutrinos - The daughter nucleus is left in an excited and unstable state |

| Electron capture with positron emission | A nucleus absorbs one orbital electron, emits one positron and two neutrinos |

| Double positron emission | A nucleus emits two positrons and two neutrinos |

| Gamma decay | Excited nucleus releases a high-energy photon (gamma ray) |

| Internal conversion | Excited nucleus transfers energy to an orbital electron and it is ejected from the atom |

Time

Time scales for nuclear related processes range from years to seconds. In the case of radioactive decay the excited nucleus can take many years () to decay (Half Life). Nuclear transitions which result in the emission of a gamma ray can take anywhere from to seconds.

Units and Dimensions

| Variable | Definition |

| 1 fermi | m |

| 1 MeV | = eV = J |

| 1 a.m.u. | Atomic Mass Unit = 931.502 MeV |

Resources

The following are resources available on the internet which may be useful for this class.

in particular

The Lund Nuclear Data Search Engine

Several Table of Nuclides

BNL

LANL

Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute

National Physical Lab (UK)

Quantum Mechanics Review

- Debroglie - wave particle duality

| Particle | Wave |

- Heisenberg uncertainty relationship

- where characterizes the location of in the x-y plane

- Energy conservation

- Classical:

- Quantum (Shrodinger Equation):

- Quantum interpretations

- E = energy eigenvalues

- = eigenvectors

- = probability of finding the particle (wave packet) between and

- = complex conjugate

- = average (expectation) value of observable after many measurements of

- example:

- Constraints on Quantum solutions

- is continuous accross a boundary : and ( if is infinite this second condition can be violated)

- the solution is normalized:

- Current conservation: the particle current density associated with the wave function \Psi is given by

Schrodinger Equation

1-D problems

Free particle

If there is no potential field (V(x) =0) then the particle/wave packet is free. The wave function is calculated using the time-dependent Schrodinger equation:

Using separation of variables Let:

Substituting we have

reorganizing you can move all functions of on one side and on the other suggesting that both sides equal some constant which we will call

Solving the temporal (t) part:

- : just integrate this first order diff eq.

Solving the spatial (x) part:

Such second order differential equations have general solutions of

- where

Now put everything together

- Notice

- the wave function amplitude does not change with time

- also, if the operator for an observable A does not change in time, then

- even though particles are not stationary they are in a quantum state which does not change with time (unlike decays).

- the term of amplitude represents a wave traveling in the +x direction while the second term represents a wave traveling in the -x direction.

- Example

- consider a free particle traveling in the +x direction

- Then

- if the particles are coming from a source at a rate of particles/sec then

Step Potential

Consider a 1-D quantum problem with the Step potential V(x) define below where

Break these types of problems into regions according to how the potential is defined. In this case there will be 2 regions

x<0

When x<0 then V =0 and we have a free particle system which has the solution given above.

- where and

x>0

separation of variables:

- Constant

The time dependent part of the problem is the same as the free particle solution. Only the spatial part changes because the Potential is not time dependent.

- Constant

If then we have a wave that traverses the step potential partly reflected and partly transmitted, otherwise it will be reflected back and the part that is transmitted will tunnel through the barrier attenuated exponentially for x>0.

Here is how it works out mathematically

For the case where :

- SHM solutions

The above Diff. Eq. is the same form as the free particle but with a different constant

- Let

Now apply Boundary conditions:

and

We now have a system of 2 equations and 4 unknowns which we can't solve.

- Notice

- The coefficient "D" in the above system represent the component of represent a wave moving from the right towards x=0. If we assume the free particle encountered this step potential by originating from the left side, then there is no way we can have a component of moving to the left. Therefore we set .

- The coefficient A represent the incident plane wave on the barrier. The remaining coefficients B and C represent the reflected and transmitted components of the traveling wave, respectively.

- Know our system of equations is

- If I assume that the coefficient A is known (I know what the amplitude of the incoming wave is) then I can solve the above system such that

similarly

Reflection (R) and Transmission (T) Coefficients

- Let

Then

- exponential decay

- Assume solution

- Recall the solution for x<0

- where

- Apply Boundary conditions

If

Then

- Continuous conditions at x=0

Assuming A is known we have 2 equations and 2 unknowns again

Reflection (R) and Transmission (T) Coefficients=

- Evanescent waves

- : Waves like which carry no current. There is a finite probability of penetrating the barrier (tunneling) but no net current is transmitted. A feature which separates Quantum mechanics from classical.

Rectangular Barrier Potential

Barrier potentials are 1-D step potentials of height (V_o > 0) which have a finite step width:

We now have 3 regions in space to solve the schrodinger equation

We now from the free particle solutions that on the left and right side of the barrier we should have

where

But in the region we have the save type of problem as the step in which the solution depends on the Energy of the system with respect to the potential. One solution for the (oscilatory) system and one for the (exponetial decay) system.

where

For the case where :

Before we set because there wasn't a wave moving to the left towards the interface. The rectangular barrier though could have a wave reflect back form the interface.

- Apply Boundary conditions

and

and

and

We now have a system of 4 equations and 6 unknowns (A,B,C, D, F and G).

But:

- : no source for wave moving to left when x>a

If we treat as being known (you know the incident wave amplitude) then we have 4 unknowns (B,C,D, and F) and the 4 equations:

Transmission

- = the transmission coefficient

To find the ration of F to A

- solve the last 2 equations for C & D in terms of F

- solve the first 2 equations for A in terms C and D

- 3.)substitute your values for C and D from the last 2 equations so you have the ratio of B/A in terms of F/A

- 1.)solve the last 2 equations

for C and D

- 2.) solve the first 2 equations for B in terms of C & D

for A in terms of C and D

- 3.) Find Reflection Coeff in terms of Transmission Coeff

or

since

Then

3-D problems

Infinite Spherical Well

What is the solution to Schrodinger's equation for a potential V which only depends on the radial distance (r) from the origin of a coordinate system?

Such a potential lends itself to the use of a Spherical coordinate system in which the schrodinger equation has the form

In spherical coordinates

- Note

so

Using separation of variables:

which we can also write as

where

Substitute

V=0

We have a constant on the right hand side so the left hand side must also be constant

- a "centrifugal" barrier which keeps particles away from r=0

substituting

In the region where V=0

The Radial equation becomes

Let

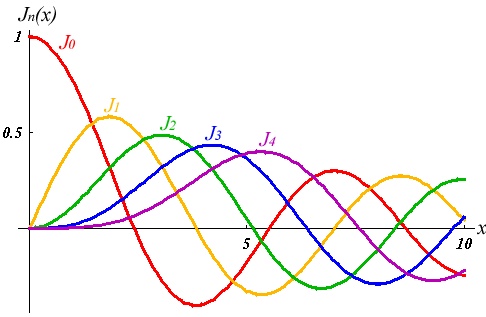

Then we have the "spherical Bessel"differential equation with the solutions:

where

and Table

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 1 | |||

| 2 | 0 | ||

| 1 | |||

| 2 |

The general solution for the 3-D spherical infinite potential well problem is

- = eigen function(s)

where

- are quantization number and quantum energy level = eigen state(s)

Energy Levels

To find the Energy eignevalues we need to know the value for "k". We apply the boundary condition

- at

to determine the "nodes" of ; ie value of so if you tell me the size of the well then I can tell you the value of k which will satisfy the boundary conditions. This means that "k" is not a "real" quantum number in the sense that it takes on integral values.

We simple label states with an integer representing the zero crossing via:

For example:

- In the case

- when

- You arbitrarily label these state as

- In the case

- Notice

- The angular momentum is degenerate for each level making the degeneracy for each energy

File:EnergyLevel3-DInfinitePotentialWell.jpg

Simple Harmonic Oscillator

The potential for a Simple Harmonic Oscillator (SHM) is:

This potential is does not depend on any angles. It's a central potential. Our solutions for Y_{l,m} from the 3-D infinite well potential will work for the SHM potential as well! All we need to do is solve the radial differential equation:

or

When solving the 1-D harmonic oscillator solutions were found which are of the form

where

If you construct the solution

Assume R(r) may be written as

substituting this into the differential equation gives

The above differential equation can be solved using a power series solution

After performing the power series solution; ie find a recurrance relation for the coefficents a_i after substituting into the differential equation and require the coefficent of each power of r to vanish.

You arrive at a soultion of the form

where

- polynomial in of degree in which the lowest term in is

these polynomials are solutions to the differential equation

if you do the variable substitution

you get

the above differential equation is called the "associated" Laguerre differential equation with the Laguerre polynomials as its solutions.

The following table gives you the Radial wave functions for a few SHO states:

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 1 |

- Note

- Again there is a degeneracy of for each

- Again E is independent of (central or constant potentials)

- if is odd is odd and if is even is even

- multiple values of occur for a give such that

- The degeneracy is because of the above points

The Coulomb Potential for the Hydrogen like atom

The Coulomb potential is defined as :

where

- atomic number

- charge of an electron

- permittivity of free space =

This potential is does not depend on any angles. It's a central potential. Our solutions for Y_{l,m} from the 3-D infinite well potential will work for the Coulomb potential as well! All we need to do is solve the radial differential equation:

or

Radial Equation

Use the change of variable to alter the differential equiation

Let

Then the differential equation becomes:

Consider the case where (Bound states)

Bound state also imply that the eigen energies are negative

Let

- Rydberg's constant

- Bohr Radius

Boundary conditions

- if is large then the diff equation looks like

To keep finite at large you need to have B=0

- if \rho is very small ( particle close to the origin) then the diff equation looks like

The general solution for this type of Diff Eq is

where A =0 so is finite

A general solution is formed using a linear combination of these asymptotic solutions

where

substitute this power series solution into the differential equation gives

which is again the associated Laguerre differential equation with a general series solution containing functions of the form

with the recurrance relation

notice that

now diverges for large .

To keep the solution from diverging as well we need to truncate the coefficients at some by setting the coefficient to zero when

This value of for the truncations identifies a quantum state according to the integer which truncates the solution and gives us our energy eigenvalues

or since \lambda is just a dummy variable

Coulomb Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues

| Spec Not. | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 1S | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2S | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2P | ||

| 3 | 0 | 3S | ||

| 3 | 1 | 3P | ||

| 3 | 2 | 3D |

The SHO and Coulomb schrodinger equations have Laguerre polynomial solutions for the radial part with the SHO solution polynomials of and the Coulomb solution polynomials linear in . The number of degenerate quantum states differs though, the SHO has 10 degenerate states while the Coulomb potential has 9 states.

Angular Momentum

As you may have noticed in the quantum solution to the coulomb potential (Hydrogen Atom) problem above, the quantum number plays a big role in the identification of quantum states. In atomic physics the states S,P,D,F,... are labeled according to the value of . Perhaps the best part is that as long as there is no angular dependence to the potential, you can reused the spherical harmonics as the angular component to the wave function for your problem. Furthermore, the angular momentum is a constant of motion because the potential is without angular dependence (central potential), just like the classical case.

The mean angular momentum for a given quantum state is given as

since has its origin in

and the uncertainty principle has

- we expect that the uncertainty principle will also impact such that

where characterizes the location of in the x-y plane.

or in other words, once we determine one component of (ie: ) we are unable to determine the remaining components ( and ).

As a result, the convention used is to define quantum states in terms of such that

This means that represents the projection of along the axis of quantization (z-axis).

- Notice

- : if then we would know and .

Intrinsic angular Momentum (Spin)

The Stern Gerlach experiment showed us that electrons have an intrinsic angular momentum or spin which affects their trajectory through an inhomogeneous magnetic field. This prperty of a particle has no classical analog. Spin is treated in the same way as angular momentum, namely

- Note

- Nucleons like electrons are also spin objects.

Total angular momentum

The total angular momentum of a quantum mechanical system is defined as

such that \vec{j} behaves quantum mechanically jusst like its constituents such that

where

In spectroscopic notation where is labeled by s,p,d,f,g,... the value of j is added as a subsript

- for example

- state with

- with

- with

In Atomic systems, the electrons in light element atoms interact strongly according to their angular momentum with their spin playing a small role (you can use separation of variables to have . In heavy atoms, the spin-orbit () interactions are as strong as the individual and interactions. In his case the total angluar momentum () of each constituent is coupled to some , you construct . When there is a very strong external magnetic field, and are even more decoupled.

- Note

- Nucleii (composed of many spin 1/2 nucleons) have a total angular momentum as well which is usually has the symbol

Parity

Parity is a principle in physics which when conserved means that the results of an experiment don't change if you perform the experiment "in a mirror". Or in other words, if you alter the experiment such that

the system is unchanged.

If

Then the potential (V(r)) is believed to conserve parity.

and

- Positive (Even) parity

- Negative (Odd) parity

- Note

- Thus if is even then is Positive parity, if is odd then is negative parity.

3-D SHO

The Radial wave functions of the 3-D SHO oscillator problem can be either positive or negative parity.

-

- Thus

-

- Thus

The conclusion is that the total wave function is positive under parity.

Parity Violation

In 1957, Chien-Shiung Wu announced her experimental result that beta emission from Co-60 had a preferred direction. In that experiment an external B-field was used to align the total angular momentum of the Co-60 source either towards or away from a scintillator used to detect particles. She reported seeing that only 30% of the particles came out along the direction of the B-field (Co-60 spin direction). In a mirror, the total angular momentum of the Co-60 source would point in the same direction as before ( while the momentum vector of the emitted particles would change sign and hence direction.

- Consequence of the experimental observation

- The Weak interaction does not conserve parity

- Parity Violation for the Strong or E&M force has not been observed

Transitions

Stable Particles

For a stable particle its wave function will be in a stationary state that is static in time. This means that if I measure the average energy of this state I will see no fluctuation because the state is stationary.

In other words

The implication of this using the uncertainty principle is that

Or in other words quantum states with live forever.

Particle Decay

If a quantum state has then it is possible for the quantum state to change (particle decay) within a finite time.

The first excited state of a nucleon (the \Delta particle) is an example of a quantum state with uncertain energy of 118 MeV

by the uncertainty principle we would expect that the particles mean lifetime would be about seconds.

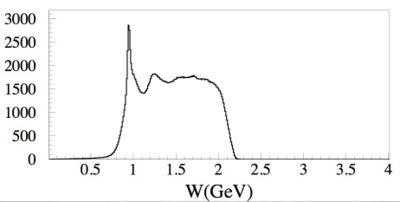

The energy uncertainty is often referred to as the width of the resonance. Below is a plot representing the missing mass (W) of a particle created during the scattering of an electron from a proton. At least two peaks are clearly visible. The highest and most left peak has a mass of about 1 GeV representing elastic scattering and the peak following that as you move to the right represents the first excited state of the proton.

The gaussian shape of the "bump" shows how this state does not have a well defined energy but rather can be created over a range of energies. The "Width" () of an exclusive distribution determined a fit to a Breit Wigner function like

where

- Center of Mass energy

- Mass of the resonance

- resonance's Width

Fermi's Golden Rule

Nuclear Properties

Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) is the fundamental quantum field theory within the standard model that is used to describe the Stong interaction of the fundamental particles known as quarks and gluons, the constituents of a nucleon, in terms of their color. While the Strong force acts directly on the elementary quark and gluon particles, a residual of the force is observed acting between nucleons within an atomic nucleus that is referred to as the nuclear force. The degrees of freedom needed to describe the elementary particles within an average Atomic nucleus with A=50 makes a solution difficult. Some of the static properties of a nucleus that a quantum field theory or model would need to predict are:

- nuclear charge and radius

- mass and binding energy

- angular momentum and parity

- magnetic dipole and electric quadrupole moments

- excited energy levels

These properties are explored further in the sections below.

Nuclear Charge and Radius

Once you know the Isotope then you know how many protons are in the nucleus of interest and therefore the charge.

The interest however is in how that charge is distributed inside the nucleus.

The density of nucleons within the nucleus tends to be uniform over a short distance and then rapidly goes to zero. There are two quantities which are used to characterize nuclear size.

- mean radius: The radius of the nucleus in which its density is half of its central value

- skin thickness: the distance over which the density of the nucleus drops from its max to its min.

Quantum measure of radius:

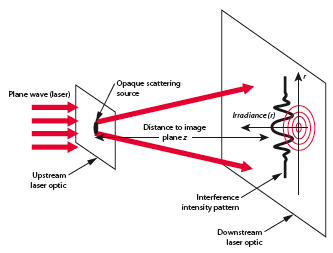

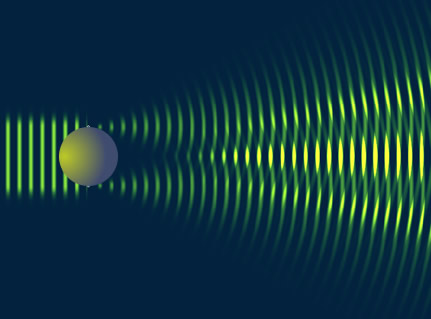

One direct method used to determine the size of an object in to alter the size of a probe until interference patterns emerge (ie ).

- Note

- The pattern broadens as .

By virtue particle wave duality, the elastic scattering of an electron from a nucleus can behave in a similar fashion to the scattering of light by an opaque target.

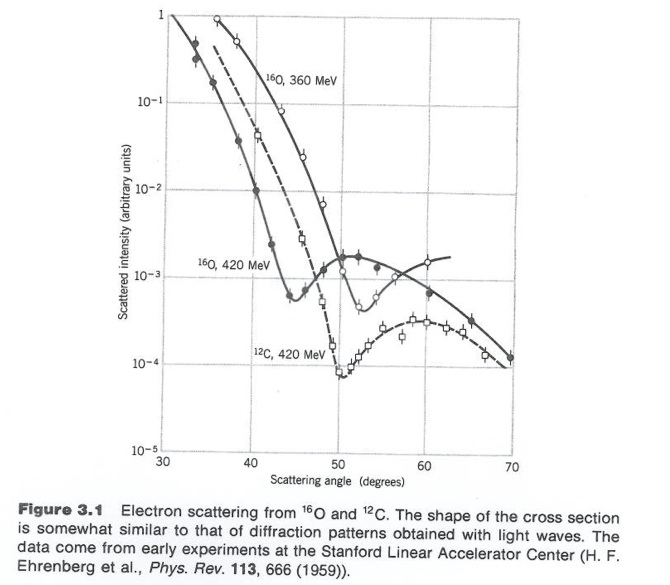

Although 3-D objects reveal diffraction patterns that are similar to those from a two dimensional disk, such comparisons are really only rough estimates. As we saw from the above, the scattering of photons from O-16 revealed a diffraction pattern. A similar diffraction pattern can be seen if you elastically scatter electrons from a Pb-208 nucleus.

Distribution of Nuclear Charge

For our current interest we would like a means to measure the distribution of charge in the nucleus of an atom. This can be accomplished by elastically scattering a probe off of the nucleus which is sensitive to charge. Elastically scattering an electron off of a nucleus is one such probe. A description of this can be found using Fermi's Golden Rule where the transition amplitude

is the main term in Fermi's Golden Rule which describes the interaction that takes place.

In our current example we have an incident electron plane wave in some initial state which gets elastically scattered by some charge distribution (a nucleus) to a final plane wave state by means of a coulomb interaction.