Difference between revisions of "Detector Geometry Simulation"

(Created page with "=Detector Geometry= Examining the geometry of the Drift Chamber, we can see that the detector is similar to a hexagonal pyramid in shape. [[File:DC_Geomentry_Sideview.png|thu…") |

|||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

[[File:PhiCone.png|thumb|center|600px|alt=Cone of constant Theta for varying Phi|'''Figure 5:''' A cone of constant Theta with varying Phi.]] | [[File:PhiCone.png|thumb|center|600px|alt=Cone of constant Theta for varying Phi|'''Figure 5:''' A cone of constant Theta with varying Phi.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =[[VanWasshenova_Thesis#DC_Super_Layer_1:Layer_1|<-Back]]= | ||

| + | =[[Detector_Geometry_Simulation|Forward->]]= | ||

=Conic Sections= | =Conic Sections= | ||

Revision as of 04:23, 4 March 2017

Detector Geometry

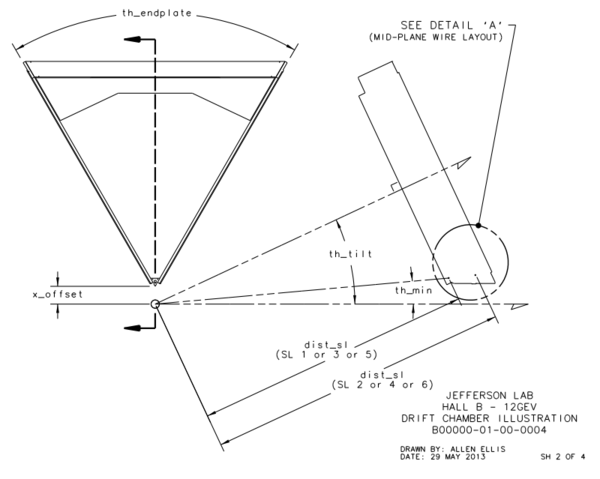

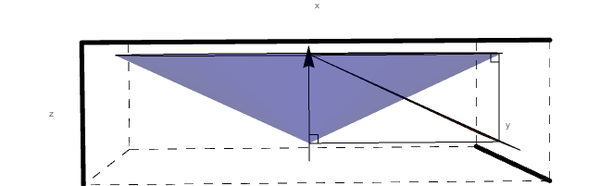

Examining the geometry of the Drift Chamber, we can see that the detector is similar to a hexagonal pyramid in shape.

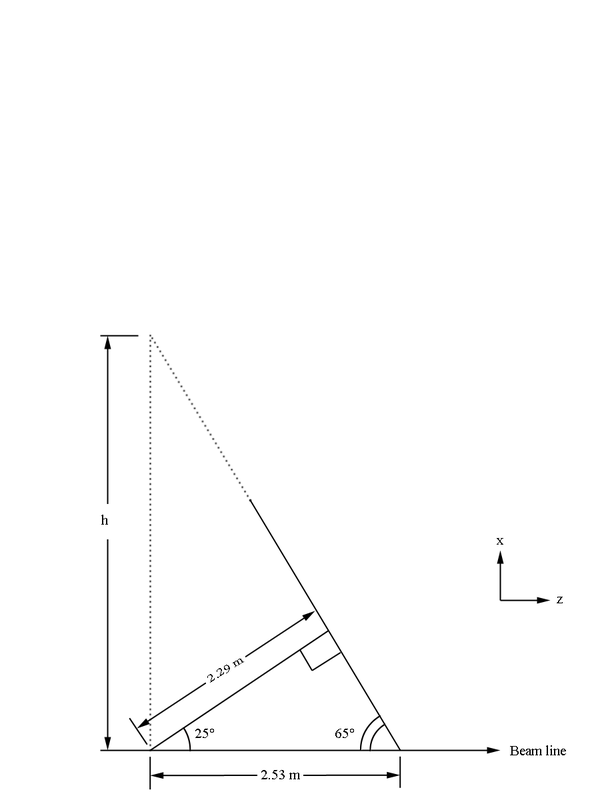

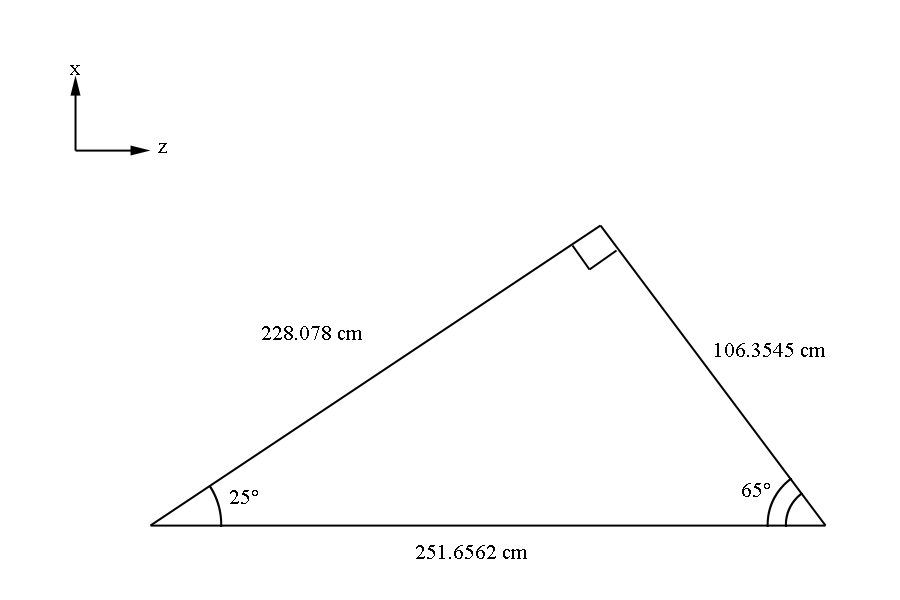

From the geometry it is given that xdist, the distance between the line of intersection of the two end-plate planes and the target position, is equal to 8.298 cm and th_min, the angle from the target vertex to the the same line, is 4.694 degrees. Using this knowledge we can simulate this situation by having the end-plate planes intersect at the beam line axis. This action in effect would grant the sector to measure angles below ~5 degrees, which we can account for by limiting angles theta within the accepted detector range. The quantity dist2tgt, the distance from the target to the first guard wire plane along the normal of said plane, is given as 228.078 cm. Using the previous understanding of the distances between planes within a Superlayer:

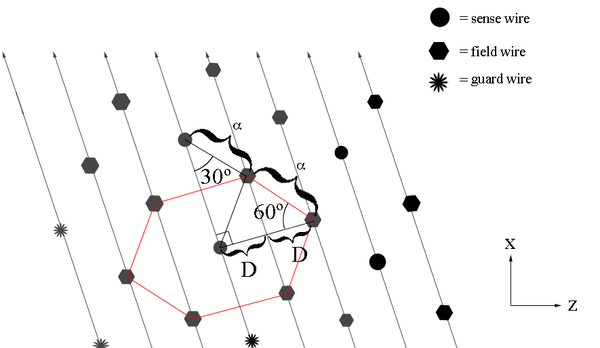

We know that the separation between levels is a constant D=.3861 cm, and that sensor layer 1 is 3 layers deep.

This gives us the distance to level 1 from the vertex (0,0,0) as 228.078 cm+3(0.3861) cm=229.2363 cm in the normal direction from the wire plane to the target. Using the fact that the wire planes are at 25 degrees to the beam line normal, we can approximate sector one as triangle that intersects with a line perpendicular to the beam line at the vertex position of (0,0,0) along the bisector of the triangle. This then by geometry shown in the figure below implies the distance traveling along the beam line would intersect the theoretical extension of the sector at z= 2.53 m. While this is beyond the physical constructs of the experimental design, we do this mathematical simplicity. This again is acceptable in that angles beyond the physical limitations of 40 degrees will not be simulated. From the geometry of a hexagonal pyramid, we can see that the quantity h should be

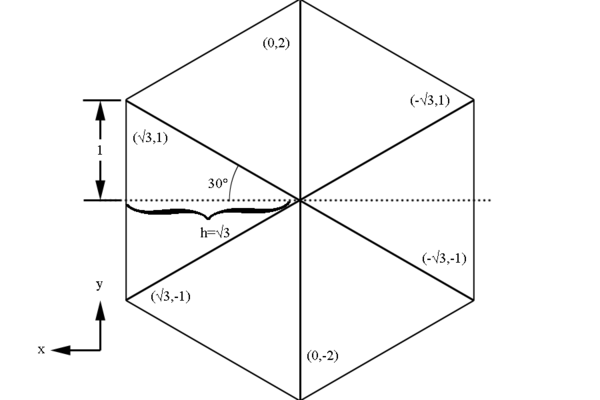

Examining the geometry of a hexagonal of h= whose coordinates are easy to calculate:

We can scale this hexagon by a factor of 3.13 to find the base of the hexagonal pyramid simulating the drift chamber geometry.

sector1=Graphics3D[{Red,Opacity[.8],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,3.13,0},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,-3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

sector2=Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[0.5],Opacity[.2],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,-3.13,0},{0,-2*3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

sector3=Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[0.5],Opacity[.2],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{0,-2*3.13,0},{-3.13\[Sqrt]3,-3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

sector4=Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[0.5],Opacity[.2],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{-3.13\[Sqrt]3,-3.13,0},{-3.13\[Sqrt]3,3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

sector5=Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[0.5],Opacity[.2],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{-3.13\[Sqrt]3,3.13,0},{0,2*3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

sector6=Graphics3D[{GrayLevel[0.5],Opacity[.2],Polygon[{{0,0,2.53},{0,2*3.13,0},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,3.13,0}}]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

Bisector0Sector1=Graphics3D[Line[{{0,0,2.53},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,0}}]];

Bisector0perpSector1=Graphics3D[Line[{{0,0,0},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,0}}]];

RightAngleVertical=Graphics3D[Line[{{.25,0,.25},{.25,0,0}}]];

RightAngleHorizontal=Graphics3D[Line[{{.25,0,.25},{0,0,.25}}]];

Bisector0Cone=Graphics3D[Line[{{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,0},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,2.53}}]];

Bisector0perpCone=Graphics3D[Line[{{0,0,2.53},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,2.53}}]];

RightAngleVertical2=Graphics3D[Line[{{3.13\[Sqrt]3-.25,0,2.53-.25},{3.13\[Sqrt]3-.25,0,2.53}}]];

RightAngleHorizontal2=Graphics3D[Line[{{3.13\[Sqrt]3-.25,0,2.53-.25},{3.13\[Sqrt]3,0,2.53-.25}}]];

BeamLine=Graphics3D[Arrow[{{0,0,-.5},{0,0,2.79}}]];

PhiCone=Graphics3D[{Blue,Opacity[.3],Cone[{{0,0,2.53},{0,0,0}},3.13\[Sqrt]3]},BoxStyle->Dashing[{0.02,0.02}],Axes->True,AxesLabel->{"x","y","z"},Ticks->None,AxesStyle->Thickness[0.01]];

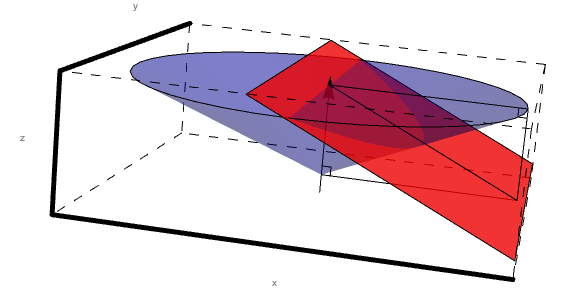

Viewing the simulation,

Show[sector1,sector2,sector3,sector4,sector5,sector6,PhiCone,BeamLine,Bisector0Sector1,Bisector0perpSector1,Bisector0Cone,Bisector0perpCone,RightAngleVertical,RightAngleHorizontal,RightAngleVertical2,RightAngleHorizontal2]

It assumed that since the Moller process does not depend on the polar angle phi, it should remain constant. When the scattering angle theta, which is measured with respect to the beam line, is held constant and rotated through 360 degrees in phi, a cone is created. Using Mathematica, we can produce a 3D rendering of how the sectors for Level 1 would have to interact with a steady angle theta with respect to the beam line, as angle phi is rotated through 360 degrees.

<-Back

Forward->

Conic Sections

Looking just at sector 1, we can see that the intersection of level 1 and the cone of constant angle theta forms a conic section.

Show[sector1,PhiCone,BeamLine,Bisector0Sector1,Bisector0perpSector1,Bisector0Cone,Bisector0perpCone,RightAngleVertical,RightAngleHorizontal,RightAngleVertical2,RightAngleHorizontal2]

Without loss of generalization, we can extend the triangle to an infinite plane to aid in viewing the conic section. Again, this falls outside of the experimental design range, but simulations would not occur in this forbidden zone.

sector1plane =

Graphics3D[{Red, Opacity[.8],

InfinitePlane[{{0, 0, 2.53}, {3.13 \[Sqrt]3, .617,

0}, {3.13 \[Sqrt]3, -3.13, 0}}]},

BoxStyle -> Dashing[{0.02, 0.02}], Axes -> True,

AxesLabel -> {"x", "y", "z"}, Ticks -> None,

AxesStyle -> Thickness[0.01]];

Show[sector1plane, PhiCone, BeamLine, Bisector0Sector1, \

Bisector0perpSector1, Bisector0Cone, Bisector0perpCone, \

RightAngleVertical, RightAngleHorizontal, RightAngleVertical2, \

RightAngleHorizontal2]

Following the rules of conic sections we know that the eccentricity of the conic is given by:

where β is the angle between the plane and the horizontal and α is the angle between the cone's base and the horizontal.

Examining the different conic sections possible we know that: